The Physics of Sorrow

Theodore Ushev

2019

| 27 min

Animation Technique – Encaustic painting

WINNER OF THE PRESTIGIOUS ANNECY CRISTAL AWARD FOR BEST SHORT FILM • 2020 ANNECY INTERNATIONAL ANIMATION FILM FESTIVAL

Selections and Awards

Cristal Award for Best Short FilmAnnecy International Animation Film Festival, Annecy, France (2020)

FIPRESCI Award for a Short FilmAnnecy International Animation Film Festival, Annecy, France (2020)

Official Selection, Canada's Top Ten of 2019TIFF - Toronto International Film Festival, Toronto, Canada (2019)

Honourable Mention for Best Canadian Short FilmTIFF - Toronto International Film Festival, Toronto, Canada (2019)

Canadian Film Institute Award for Best Canadian AnimationOttawa International Animation Film Festival, Ottawa, Canada (2019)

Best Short Film & Best Animated Short Film Festival du nouveau cinéma - FNC, Montreal, Canada (2019)

Honourable Mention in the Best Canadian Short Film Category Vancouver International Film Festival, Vancouver, Canada (2019)

Golden Spike for Best Short FilmValladolid International Film Festival, Valladolid, Spain (2019)

Official SelectionAnimafest Zagreb – World Festival of Animated Film, Zagreb, Croatia (2020)

Winner, Director – Fiction / Winner, AnimationYorkton Film Festival, Yorkton, Saskatchewan, Canada (2020)

More Selections and Awards

“I have always been born. I am us.”

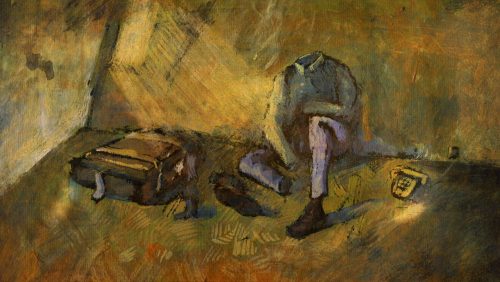

We are all immigrants. Some leave cities or countries, all of us leave our childhood. Like the Minotaur of mythology, we roam through personal labyrinths, carrying nothing but a suitcase of memories, a portable time capsule filled with assorted mementoes from a past we can no longer reach.

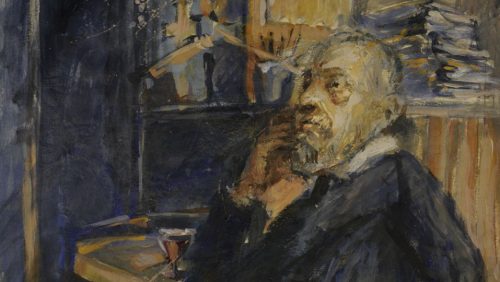

The first fully animated film made using the encaustic-painting technique, The Physics of Sorrow, inspired by the novel by Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov, tracks the outlines of an unknown man’s life as he sifts through memories of circuses, bubble-gum wrappers, first crushes, army service from his youth in communist Bulgaria, and an increasingly rootless and melancholic adulthood in Canada—all the while struggling to find home, family and self.

Navigating a maze of fleeting thoughts and emotions, The Physics of Sorrow is a potent portrait of a dislocated generation as they move through everchanging personal and geographic landscapes.

Superbly drawn and animated by Academy Award® nominee Theodore Ushev (Blind Vaysha, Lipsett Diaries), each image in The Physics of Sorrow is a work of art, aptly evoking the mesmerizing existence of its nostalgic protagonist.

Narrated by Rossif Sutherland, with a special guest-voice appearance by Donald Sutherland, The Physics of Sorrow ranks as Theodore Ushev’s most ambitious, intimate and poignant film to date. A National Film Board of Canada production with the participation of ARTE France.

We are all immigrants. Some leave cities or countries, all of us leave our childhood. Like the Minotaur of mythology, we roam through personal labyrinths, carrying nothing but a suitcase of memories, a portable time capsule filled with assorted mementoes from a past we can no longer reach.

The first fully animated film made using the encaustic-painting technique, The Physics of Sorrow, inspired by the novel by Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov, tracks the outlines of an unknown man’s life as he sifts through memories of circuses, bubble-gum wrappers, first crushes, army service from his youth in communist Bulgaria, and an increasingly rootless and melancholic adulthood in Canada—all the while struggling to find home, family and self.

Superbly drawn and animated by Academy Award® nominee Theodore Ushev (Blind Vaysha, Lipsett Diaries), each image in The Physics of Sorrow is a work of art, aptly evoking the mesmerizing existence of its nostalgic protagonist.

One-Liner & Two-Liner

Two-liner

The Physics of Sorrow tracks an unknown man’s life as he sifts through memories of his youth in Bulgaria through to his increasingly rootless and melancholic adulthood in Canada.

One-liner

The Physics of Sorrow is a potent portrait of a dislocated generation struggling to find home as they shift through everchanging personal and geographic landscapes.

Description of Animation Technique

The Physics of Sorrow is the first fully animated film made using the encaustic-painting technique, also known as hot-wax painting. This technique, which dates back to antiquity, involves using heated beeswax and then adding coloured pigments. The liquid or paste is then applied to a surface (wood, canvas, etc.).

The technique was used in mummy portraits from Egypt and later by contemporary artists like Jasper Johns, Tony Scherman and Fernando Leal Audirac.

In applying the encaustic-painting technique to create The Physics of Sorrow, Theodore Ushev mixed slightly bleached beeswax with pigments. “It was an old recipe that my father gave me,” says Ushev. He then painted the ingredients onto paper and let it dry out. “After that,” adds Ushev, “I make it hot so that it becomes liquefied. Then I can change the movement and colours. It’s very physically demanding. You have to paint very fast because the hot wax dries out quite quickly.”

Using encaustic painting was not a random choice for Ushev. “The first time capsules were the Egyptian tombs and coffins. They would put everyday objects alongside the buried person with an encaustic portrait on top of it. Encaustic was the first technique used to create realistic portraits of the dead on Egyptian sarcophagi, thus allowing the memory of the buried person to be preserved over centuries. With The Physics of Sorrow, I wanted to create a sarcophagus of my generation.”

INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR THEODORE USHEV

This is your second collaboration with Georgi Gospodinov, the first being the Academy Award®-nominated Blind Vaysha, which was adapted from a Gospodinov short story. What was it about his book, The Physics of Sorrow, that resonated so strongly with you?

A few years ago, on vacation in Bulgaria, I bought the book. When I came back to Montreal I started reading it one evening, and I couldn’t get back to sleep until the last page was turned. It resonated deeply; it was like reading not only my own life, but also the life of a whole generation. I saw it immediately as a film—as a time capsule of our time, painted in the oldest and most durable painting technique.

There are elements of autobiography in the film, but it really seems to be more about a certain generation of people than one specific person. You would be deemed a member of the so-called Generation X. Do you believe generations have certain traits in common, distinguishing us from previous ones?

Every generation, including Gen X, to which I belong, has its own code of reading. We were born in a time full of hope—probably the most optimistic and joyful in the whole century—the world was changing, alive and psychedelically colourful. We entered our active lives in another extremely optimistic time (the end of the Cold War). Despite all this, we failed to create a better world, and now we are in a world ruled by incompetent, hateful and arrogant leaders. How a generation raised in love of liberty, freedom and compassion surrendered to radical alt-right morons is beyond my understanding.

You’ve dedicated the film to your father, who passed away in 2018. Can you say a few words about his influence on you as an artist?

His influence on me was mostly in his life philosophy—he was gentle and kind, but very strong at the same time. He had to struggle against the totalitarian Communism and censorship that ruled Bulgaria in his lifetime. He spent his life painting visionary abstract technological paintings, despite the dominant ideology of Socialist Realism and the attacks of state functionaries. I can only imagine the price he paid for this resistance. His notion that you must never compromise your art, no matter what obstacles you face, no matter how difficult your situation, will stay with me forever.

It’s also interesting that the father and son theme is reflected in your choice of narrators. This was obviously a conscious decision. Why did you feel it was necessary to have real-life fathers and sons participate?

It was an instinctive decision—actually, it was my producer, Marc Bertrand, who suggested that we use Xavier’s father, Manuel Tadros, as an additional voice—the circus presenter (Manuel is a longtime collaborator with the Cirque du Soleil.) Then, while we were recording him, someone came up with the idea of adding more fathers. And then everything came together. Suddenly, it became about the complexities of father-son relationships, like in Greek mythology. With sons of artists, there is always an inferiority complex, the idea that you’ll never be as good as your father. You can feel this in all three of us: me, Rossif, and Xavier. We all dealt with it in our own way, through rebellion or denial. Rossif never wanted to become an actor; it was by chance that his immense acting talent was discovered (this was not the case with Xavier, obviously, who was a child prodigy). And me? I refused to become a painter, even though I love painting. I took a parallel road as an animator-director, so my work can’t be directly compared with my father’s paintings. This is the labyrinth that we all had to find our way through, to kill the Minotaur in us.

In the film, you say that we are all immigrants. What do you mean by that?

I’ve had many conversations with other immigrants, and I often sense an inexplicable nostalgia in them for their past—for Communist life, or another country, or the small villages they came from. They tend to put a “shine” on their memories, polishing up a life that wasn’t really that pleasant. It was then that I realized that their nostalgia was solely connected to their childhood, youth, emotions, loves. Nostalgia seems more connected to memories of events and objects, not places.

Why did you choose to use this encaustic painting technique for The Physics of Sorrow?

Encaustic is one of the earliest known painting techniques. The Egyptians used it for portraits that were buried with the deceased, in tombs that were the first time capsules—they contained objects used by the person in his daily life. Conceptually, encaustic was an obvious choice. But no one had used it for animation, so I had to invent the technique. The first scenes were an absolute disaster. Then it suddenly came, and became my technique when I used a recipe that my father had given to me for mixing the wax with the pigment. I was then able to paint 50 frames a day, with great detail in every image.

This is your longest and most ambitious film to date. There is so much interesting material in the book The Physics of Sorrow that I imagine this could have easily been a feature film. Did you have to make some painful creative sacrifices to keep the running time down?

Yes, I did. It could easily have been a feature. But I liked the shorter form. I hate the way distribution, screenings, and festivals can dictate form; it’s a trap. The film length shouldn’t be connected to some standard model—it should be the length that I need to tell the story and arouse the viewer’s emotions.

The Minotaur myth is a big part of Gospodinov’s novel; what does the Minotaur represent to you?

We live in a labyrinth. We are punished, but we are not guilty. The Minotaur was guilty of no crime in being the bull’s son. And I bear no guilt for being raised in the cave of a Communist country, or being the child of an artist. The dream of every Minotaur in this world is to get out of the labyrinth, out of the cave, to see the sun, to be a happy person. This is a film about the quest for happiness of all the Minotaurs in the world. “I am us.”

Promotional Materials

Trailer

Clips

The Technique (Making-of)

Images

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Director Theodore Ushev - Additional Photos

Loading...

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Download

Loading...

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Download

Loading...

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Download

Loading...

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Download

Loading...

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Download

Loading...

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Download

Loading...

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Photo: Stephan Ballard

Download

Team

Theodore Ushev

Director

Photo

Photo : NFB

Marc Bertrand

Producer

Photo

Photo : Stephan Ballard

Julie Roy

Executive Producer (NFB)

Photo

Credits

The National Film Board of Canada

with the participation of ARTE France

presents

The Physics of Sorrow

A film by

Theodore Ushev

Based on the book The Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov

With the voice of

Rossif Sutherland

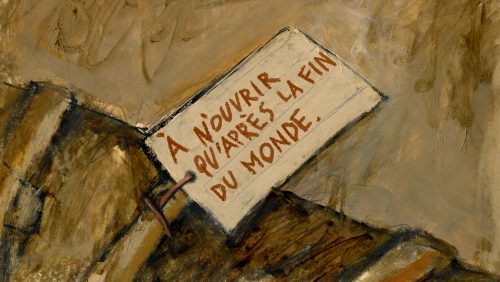

Sometimes the end of the world is a purely personal matter…

In memory of my father

Production

Marc Bertrand

Sound Design

Olivier Calvert

Additional voices

Donald Sutherland

Manuel Tadros

Theodore Ushev

Consultants

Anca Damian

Georgi Gospodinov

Translation

Helge Dascher

Karen Lynn Houle

Revision

Mélanie Gleize

Copyright Clearance

Sylvia Mezei

With the participation of ARTE France

Cinema Department

Short Film Program Manager: Hélène Vayssières

Acknowledgements

Natalie Hamel Roy

Maxwell Diggory

Martin Delisle

Alexandra Ushev

Music

Shitty City

Yesterday’s Fire

Composed by: Spencer Krug, Risto Joensuu, Markus Joensuu, Saku Kämärälinen, Matti Ahopelto

Performed by: Moonface

With permission from Third Side Music

Hungarian Quick March

Composed by: Franz Listz

Performed by: Central Wind Orchestra of the Hungarian Army

With permission from Naxos of America, Inc.

The Safety Dance

Composed by: Ivan Doroschuk

Performed by: Men Without Hats

With permission from Universal Music Publishing Canada and Marc Durand Productions

Fuga

Composed by: Nikola Gruev

Performed by: Kottarashky

With permission from Asphalt Tango Records

The Hebrides, Op. 26, Fingal’s Cave

Composed by: Felix Mendelssohn

With permission from Naxos of America, Inc.

Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D 759/ Rosamunde

Composed by: Franz Schubert

With permission from Naxos of America, Inc.

Tous les garçons et les filles

Composed by: Françoise Hardy, Roger Samyn

Performed by: Françoise Hardy

With permission from Sony Music Entertainment and Les Éditions Ad Litteram

Sound Archives

National Film Board of Canada

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

Technical Direction

Pierre Plouffe

Eric Pouliot

Technical Specialist

Yannick Grandmont

Technical Coordination

Jean-François Laprise

Foley

Nicolas Gagnon

Foley Recording

Geoffrey Mitchell

Mix

Isabelle Lussier

Online Editing

Serge Verreault

Associate Producers

Anne-Marie Bousquet

Mylène Augustin

Administrators

Diane Régimbald

Karine Desmeules

Senior Production Coordinator

Camila Blos

Studio Coordinators

Michèle Labelle

Laetitia Seguin

Marketing

Geneviève Bérard

Executive Producer

Julie Roy

Animation Studio

Programming and Production, French Program

Creation and Innovation

www.nfb.ca

© 2019 National Film Board of Canada

Media Relations

-

About the NFB

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) is a leader in exploring animation as an artform, a storytelling medium and innovative content for emerging platforms. It produces trailblazing animated works both in its Montreal studios and across the country, and it works with many of the world’s leading creators on international co-productions. NFB productions have won more than 7,000 awards, including seven Oscars for NFB animation and seven grand prizes at the Annecy festival. To access this unique content, visit NFB.ca.