Standing on the Line

Paul Émile d'Entremont

2018

| 80 min 30 s

Selections and Awards

Official SelectionDOXA Documentary Film Festival, Vancouver, British Columbia (2019)

Official SelectionFIN Atlantic International Film Festival, Halifax, Nova Scotia (2019)

Official SelectionCalgary International Film Festival, Calgary, Alberta (2019)

Official SelectionCinéfest Sudbury International Film Festival, Sudbury, Ontario (2019)

Official SelectionParrsboro Film Festival, Parrsboro, Nova Scotia (2019)

In both amateur and professional sports, being gay remains taboo. For some athletes, the pressure to perform is compounded by the further strain of deciding whether or not to come out of the closet. They set out to overcome prejudice in the hopes of changing things for the athletes of tomorrow.

Watch the Film

SHORT SYNOPSIS

In both amateur and professional sports, being gay remains taboo. Few dare to come out of the closet for fear of being stigmatized, and for many, the pressure to perform is compounded by a further strain: whether or not to affirm their sexual orientation.

Breaking the code of silence that prevails on the field, on the ice and in the locker room, this film takes a fresh and often moving look at some of our gay and lesbian athletes, who share their experiences with the camera. They’ve set out to overcome prejudice in the hopes of changing things for the athletes of tomorrow.

LONG SYNOPSIS

Behind every sporting feat, there’s an athlete. And behind the athlete can be someone who has seen or experienced discrimination based on sexual orientation. While a handful of athletes in the sports hall of fame are openly and proudly gay, in a culture that prizes virility, toughness and heterosexuality, the pressure to perform can be compounded by the further strain of deciding whether or not to come out of the closet.

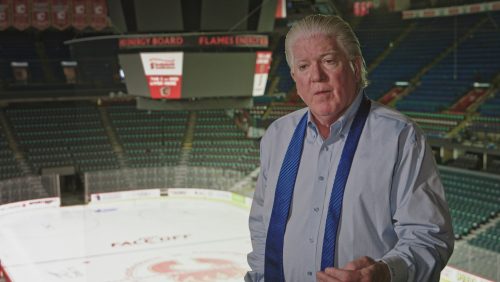

Standing on the Line sets out to break the code of silence that reigns in amateur and professional sports. To the backdrop of a New Brunswick varsity football team in training, filmmaker Paul Émile d’Entremont takes a fresh look at some of our top athletes, who’ve joined their voices in support of the LGBTQ cause. We meet Canadian speed skater Anastasia Bucsis, who represented Canada in Sochi; former Montreal Impact player David Testo; and hockey personalities like Brock McGillis, the first pro men’s goalie to come out publicly, and Brendan Burke, whose 2009 coming out rocked the world of pro sports. Burke’s tragic death the following year sparked the creation of You Can Play, a campaign advocating tolerance and inclusion for which his brother Patrick and his father—hockey legend Brian Burke—are the proud ambassadors. Hoping to change things for tomorrow’s athletes, they’re slowly breaking through the last taboo: homophobia in sports.

About the Film

The world of amateur and professional sports is fertile ground for homophobia. In an ostensibly heterosexual culture that idolizes virility and toughness, gay and lesbian athletes can fall victim to exclusion, both directly and indirectly. In recent years, however, some have decided to stop pretending and—in the hopes of changing things for tomorrow’s players—do what few have dared: namely, publicly come out.

While still a taboo topic in the locker room, the issue of gay athletes in sports is the focus of Paul Émile d’Entremont’s documentary Standing on the Line. Top athletes go on camera to break the code of silence as, in the background, we watch the Olympiens—the varsity football team at École secondaire L’Odyssée in Moncton, New Brunswick—undergo their gruelling training.

For some athletes, disclosing their sexual orientation can have repercussions on their mental and physical health. There are the insults and slurs to contend with, and the delicate issues of locker-room privacy, nudity in the showers, sharing hotel rooms; and then there are the narrow-minded fans who spread rumours. There’s also the spectre of failure and with it, the need to protect image and reputation, manage sensitivities and egos, maintain group cohesion and not jeopardize the team’s mission; these are just some of the reasons that could keep an athlete in the closet.

But for others, coming out is liberating. Take Anastasia Bucsis, a Canadian speed skater whose entourage took the news in stride. She first came out to her family and friends at the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Then, a few months before Sochi 2014, with Russia banning gay “propaganda,” Anastasia came out publicly—making her the only openly gay North American Olympian at the time. “At last I could be myself,” she said. Following her announcement, the skater saw her performance improve dramatically. During qualifications for the 2018 Games in Pyeongchang, she said: “[Standing] up and saying, ‘Yeah, I’m gay’… really gave me a sense of pride.”

Like Bucsis, other athletes are proud to lend their names to the LGBTQ cause, including David Testo, former soccer player for the Montreal Impact. Testo publicly revealed his orientation in 2011, a pivotal year for the team, at the time poised to enter Major League Soccer. Though his sexuality was no secret to his managers or teammates, Testo was assailed by on-field slurs. “To talk about this, it’s bigger than winning or losing,” he says. Everything changed after he came out, resulting in him hanging up his cleats and retiring prematurely. Lacking a safety net, Testo underwent a dark period marked by drugs and alcohol. Today, though, he makes no bones about his identity.

Brock McGillis is a former goalie who hid his sexual orientation from his teammates, going so far as to forge a reputation as a womanizer. No players in the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League (QMJHL) or National Hockey League (NHL) had ever openly discussed their orientation; McGillis feared being given less ice time or even getting kicked off the team. Today, he gives back to the sport by training young Canadian hopefuls, and he also tours schools. His mission: change the culture of homophobic language that continues to run rampant within the sport. And his efforts are paying off, as witnessed by his remarkable meeting with the Saint John Sea Dogs. Following the encounter, the Sea Dogs became the first Q-league member to partner with You Can Play, a campaign promoting inclusion and safety for all LGBTQ athletes, coaches, associations and supporters.

You Can Play came into being following the tragic death of Brendan Burke in a car crash in 2010, just a year after his coming out had rocked the sports world. His father, former Maple Leafs general manager Brian Burke, and his brother Patrick, who co-founded the campaign, wanted to honour his legacy. Patrick has expressed regrets about “not doing my job as a big brother” as he should have: “I made gay jokes, I made homophobic comments.” Culturally and socially, nothing to date has proven as effective for promoting awareness as hockey.

With Standing on the Line, filmmaker Paul Émile d’Entremont delivers a standout work whose message lingers long after the film ends. Besides showing that there’s still much work to be done, the documentary is permeated with a strong desire for change, as evidenced by the striking scene between football coach Serge Bourque and his assistant Justin Boisvert. After witnessing blatant homophobia within their team, they summoned the players to an emergency meeting the night before a big game. “If you go out there tomorrow with an attitude of inclusion, not only will you win the game, but you’ll also win in life,” said Bourque, who lost his gay brother to suicide. The Olympiens won, their game marked by solidarity as never before. Being gay, it would appear, is no deterrent to team spirit.

Interview with Paul Émile d’Entremont

What made you want to make this documentary?

If you’re going to spend years on a film, you’d better find an idea you’re passionate about, one that resonates with you on a personal level. My sexual identity is what most defines me. Today this “difference” plays a major role in and is central to all my projects.

Last Chance (2012, NFB) chronicles the hurdles faced by five LGBTQ individuals seeking asylum in Canada. Our country is a beacon for exiles like these who seek refuge in Western society. Standing on the Line grew out of my desire to explore new ground: homophobia in sports. I’m not particularly athletic and so the film also became an opportunity to face some demons.

Why are homophobic acts on the rise in sports?

Very often it’s out of ignorance. Young people are being bullied because of their sexual orientation. High school was therefore the obvious choice for exploring this subject. The documentary not only reminds us that it’s hard to be a gay athlete, but that there are also solutions and role models. In that sense, I was really inspired by École L’Odyssée in Moncton, New Brunswick. I would have liked to have gone to a school like that.

What makes L’Odyssée so special?

L’Odyssée was one of the first high schools to implement the Indigo project. Principal Alain Bezeau took decisive action to deal with the bullying in his institution. “There’s no way things in my school are going to be the same as they were 20 years ago.” The project also runs in a number of English-language high schools under the Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA). It’s a safe, non-judgemental space where students can discuss sexual identity freely. A place where freedom of speech prevails. Young people can talk about sexuality openly and intelligently. In a group meeting, a student referred to people who think heterosexuality is the only possible sexual orientation, saying, “We live in a heteronormative society.” They’ve got the jargon!

Was it hard to find athletes to agree to go on camera?

I presented my project at a number of school board meetings. Some were uncomfortable with the topic and turned me down. At long last, the Francophone Sud School District opened its doors to me, which is where I heard about L’Odyssée. The school had a number of great things going for it, including the Indigo project. Still, getting assistant coach Justin Boisvert (who trains the school’s team, Les Olympiens de Moncton) and former player Jean-Christophe Comeau to talk on camera wasn’t without challenges. Before they came on board, I really had to stress the project’s importance and scope. I also had to point out that the documentary would be around for a while. It’s a film, and a film leaves traces…

As for the pro athletes, they’d already come out long ago. Still, for David Testo, the former Montreal Impact player who came out in 2011, it wasn’t easy. He kept putting off our meetings. Going back to unresolved things from his past was frightening. The mere idea of setting foot in the high school where his talent first came to light stirred up a lot of strong feelings. After the shoot, he said: “I knew it would be hard, but I’m really happy I did it.” The experience was intense.

Do you think the sports world lags behind other professions in terms of its openness to talking about sexual orientation?

When I compare it to other fields, I’m inclined to say yes. For example, why have no active or retired NHL players come out of the closet yet? Obviously, there have to be gay players in the NHL. They’re known to their teammates, but it’s never made public. Some gay players, even the most talented, will end up quitting their sport, since there’s a certain pressure to come out publicly.

In your opinion, which sport will do the most for raising awareness?

While I can’t single out any one sport, it would certainly be team sports. You need a celebrity to break through the barriers and bring about real change.

Does coming out have an impact on a player’s ability to succeed?

You can’t tell an athlete, “Oh, just come out of the closet and everything will be fine.” Think of David Testo, who quit soccer after he came out. On the other hand, speed skater Anastasia Bucsis saw her performance improve once she publicly identified as gay. The same goes for Canadian swimming legend Mark Tewksbury, today a gay and lesbian rights activist, who was a consultant for this film. He came out in the late 1990s and his performance also improved once he did. But there’s still much work to be done in this area, which is why I made the film.

In sports, do women have an easier time being open about their sexual orientation than men?

Gay female athletes are subject to a different kind of pressure. In fact, they have to cope with two forms of discrimination: one for being a lesbian, the other for being a woman. The difficulty is essentially the same, as we can see in sports that have judges. In figure skating, for example, effeminate men, or women whose appearance is more masculine, may be judged more severely. Traditional gender stereotypes are still very much rooted in the collective imagination.

Do you think it’s best for an athlete to come out before, during or after their career?

There are many factors to consider, particularly whether or not the athlete is well supported. Former semi-pro goalie Brock McGillis, for example, waited till he’d stopped playing. He has said: “I was pushed to become an activist and spokesperson at a time when I didn’t even know how to be gay!” In football, there was American rookie Michael Sam, who rejoined the Montreal Alouettes in 2015 and who has discussed how coming out affected his professional career.

Does coming out amount to putting the individual before the team?

This is a false belief about team sports. In the locker room or on the field, you often hear: “We can’t let this distract us.” David Testo talks candidly about the locker room and says that in all his years of playing soccer, he never felt at ease. Some of his teammates even wore their underwear when they took their showers in front of him. But the idea that being gay hinders performance or prevents the team from winning belongs to another era.

Do you think the homophobia in amateur and pro sports reflects the homophobia in society?

In sports as in life, homophobia reflects a problem in our society. It first shows up in the family sphere, regardless of religion. From there it spills over into school, sports or the workplace. Large cities, seen as havens of anonymity, are wrongly assumed to be the place to come out and find refuge against homophobia. But in fact, many people still refuse to reveal their “difference” to their boss, colleagues and entourage. Things are changing, but change takes time. There is hope; but there have been setbacks, as seen in some countries, including Russia and the U.S., where anti-gay laws are gaining ground. The notion of openness is not universal and this leads to restricted attitudes, thoughts in a vacuum.

You got to meet Brian Burke, former general manager of the Toronto Maple Leafs. Can you tell us a little about this hockey legend?

During one interview, Brian Burke talked about his son, Brendan Burke, who was tragically killed in a car crash. Brendan’s coming out had the effect of a bomb being dropped in the hockey world. Brian also discussed the gay community with a great deal of insight. His other son, Patrick, commented: “We’ve built up this idea of athletes as warriors. We really don’t train young athletes to put themselves in other people’s shoes.” Father and son have joined forces to broadcast a strong message through their involvement in You Can Play, an inclusion project aimed at athletes, coaches, athletic associations and LGBTQ champions.

What impact would you like your film to have?

In addition to wanting it to reach people on an emotional level, I want the film to be used as an awareness-raising tool for schools and sports teams. I hope it helps to get the conversation started. I also hope it makes viewers think.

What would you say to young amateur or pro athletes who are hesitant to reveal that they’re gay?

Sports is important. It’s beautiful. You have to choose the right moment to come out. You need to make sure you have solid support, particularly from those around you. The experience can be very liberating. Still, even once you’ve made the announcement, the process of coming out is never over.

Trailer

Clip 1

Clip 2

Clip 3

Clip 4

Clip 5

Promotional Materials

Team

Paul Émile d’Entremont

Director

Photo

Photo : Mario Paulin

Christine Aubé

Producer

Photo

Photo : NFB

Jac Gautreau

Producer

Photo

Photo : Karine Wade

Maryse Chapdelaine

Producer

Photo

Photo : NFB

Images

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Credits

Producers

Christine Aubé

Jac Gautreau

Maryse Chapdelaine

Executive Producers

Michèle Bélanger

Dominic Desjardins

Editor

Dominique Sicotte

Director of Photography

Mario Paulin

Music

Serge Nakauchi Pelletier

a film by

Paul Émile d’Entremont

With the participation of

Anastasia Bucsis

Anita Bucsis

David Testo

Judy Testo

Brock McGillis

Brian McGillis

Serge Bourque

Jean-Christophe Comeau

Justin Boisvert

Kaylin Irvine

Patrick Burke

Brian Burke

Alain Bezeau

Trevor Georgie

Justin Roberts

Written and directed by

Paul Émile d’Entremont

Research

Paul Émile d’Entremont

Nancy Marcotte

Director of Photography

Mario Paulin

Additional Camera

François Vincelette

Jimmy D. Houssen

With the help of

Daniel Greenwood

Mark Moore

Location Sound

Serge Arseneault

Georges Hannan

Simon Doucet

Marc Landry

Mathieu Babin

Production Managers

Nancy Marcotte

Michelle Paulin

Jean-Michel Vienneau

Editor

Dominique Sicotte

Editing Assistant

Justin Morand

Sound Design

Mélanie Gauthier – Studio SOUNDCHICK SFX

Dialogue Editor

Sandy Pinteus

Sound Mixer

Jean-Paul Vialard

Online Editor

Serge Verreault

Infographics and Titles

Mélanie Bouchard

Transcription Services

Pro Documents

MELS

Subtitles

MELS

Foley

Simon Meilleur

Foley Recording

Luc Léger

Archival Research and Rights Clearance

Nancy Marcotte

Archives

AP Images

Bell Media

Getty Images

The Canadian Press

National Post, a division of Network Postmedia Inc.

NHL Network

Olympic Oval / University of Calgary

Personal photographs : Brock McGillis, Anastasia Bucsis, David Testo, The Burke Family

Reuters

Société Radio-Canada / CBC

The Globe and Mail

Todd Korol

TSN

You Can Play Project

Original Music

Serge Nakauchi Pelletier

© 2018 National Film Board of Canada (SOCAN) / Ho-Tune Musique (SOCAN)

Original Song

AGAIN (AFTER ECCLESSIASTES)

written and composed by David Lang © Red Poppy, Ltd.

interpreted by Theatre Of Voices, Ars Nova Copenhagen

conducted by Paul Hillier

courtesy of Harmonia Mundi / [PIAS]

A special thanks to Mark Tewksbury

Thanks to

Matt Allen

Jennifer Birch-Jones

Valérie Beauquier

Stéphanie Bourque

Line Chamberland

Reno Chouinard

Robert Christian

Pascal Clément

Isabelle Cormier-LeBlanc

Wade Davis

Anne et Jean Bernard d’Entremont

Guylaine Demers

Nick De Santis

Jonathan Diodati

Marlene Edoyan

John Fennell

Carmen Garcia

Justin Guitard

Monique Hébert-Savoie

George Hope

Bonnie Johnston

Ricky Landry

Steve Lapierre

Luc Léger

Sylvain l’Espérance

Natacha Llorens

Rob Mabee

Cheryl MacDonald

Sheldon McIntosh

Monia Morrissette

Jason Pelletier

Ariane Pétel-Despots

Shannon Rempel

Marie-Lise Sicotte

Darko Stipic

Jordan Timmons

Jeffrey Truchon-Viel

Dina Tsoulouhas

Mauricio Velasco

David Vink

Rob Wilcher

Jay Wheaton

Margo Wheaton

Indigo Committee, L’Odyssée School, Moncton, New Brunswick

France Breault, social worker

Sabrina Bernard

Finn Condé

Jo-Annie Levesque

Gabrielle Michaud

Jessica Pond

Julie Rennison

Elise Smith

Saint John Sea Dogs, New Brunswick

Tim Roszell, Manager of Media and Communications

Stewart Bagnell

Anthony Boucher

Robbie Burt

Nick Deakin-Poot

Alex D’Orio

Alexis Girard

Matt Green

Aiden MacIntosh

Kevin Mason

Brendan O’Reilly

Cédric Paré

William Poirier

Ben Reid

Ostap Safin

Radim Salda

Tyler Smith

Bailey Webster

Matt Williams

Luke Wilson

And also

Fairmont Banff Springs

Francophone South School District, New Brunswick

Gerry McCrory Countryside Sports Complex, Sudbury

Killarny-Glengarry Community Association, Calgary

L’Odyssée Olympians

L’Odyssée School. Moncton

Moksha Yoga Montreal

Montreal Impact

T.C. Roberson High School

University of Calgary

Woody’s, Toronto

Zero Gravity Climbing and Yoga, Montreal

Marketing Managers

Karine Sévigny

Judith Lessard-Bérubé

Administrator/Line Producer

Geneviève Duguay

Production Coordinator

Audrey Rétho

Technical Coordinator

Daniel Claveau

Video Technical Support

Patrick Trahan

Pierre Dupont

Isabelle Painchaud

Audio Technical Support

Bernard Belley

Legal Counsel

Christian Pitchen

Producers

Christine Aubé

Jac Gautreau

Maryse Chapdelaine

Executive Producers

Michèle Bélanger

Dominic Desjardins

French Program

Canadian Francophonie Studio – Acadie

A production of

The National Film Board of Canada

© 2018 National Film Board of Canada

Media Relations

-

About the NFB

Founded in 1939, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) is a one-of-a-kind producer, co-producer and distributor of engaging, relevant and innovative documentary and animated films. As a talent incubator, it is one of the world’s leading creative centres. The NFB has enabled Canadians to tell and hear each other’s stories for over eight decades, and its films are a reliable and accessible educational resource. The NFB is also recognized around the world for its expertise in preservation and conservation, and for its rich and vibrant collection of works, which form a pillar of Canada’s cultural heritage. To date, the NFB has produced more than 14,000 works, 7,000 of which can be streamed free of charge at nfb.ca. The NFB and its productions and co-productions have earned over 7,000 awards, including 11 Oscars and an Honorary Academy Award for overall excellence in cinema.