Ninth Floor

MINA SHUM

2015

| 81 min

“Another great doc, more proof of the value of the National Film Board.”

– Now Magazine

“With carefully focused artistic merit, Ninth Floor is worthy of TIFF accolade.”

– Toronto Star

“… the overall effect is a powerful and essentially poetic challenge to a culture

still not quite over its primitive fear of the ‘others’ who, in fact, make this a country.”

– The Georgia Straight

Short Synopsis

It started quietly when a group of Caribbean students, strangers in a cold new land, began to suspect their professor of racism.

It ended in the most explosive student uprising Canada had ever known.

Over four decades later, Ninth Floor reopens the file on the infamous Sir George Williams Riot – a watershed moment in Canadian race relations and one of the most contested episodes in the nation’s history.

Making a compassionate and audacious foray into non-fiction, writer and director Mina Shum locates the protagonists in clandestine locations throughout Trinidad and Montreal, the wintry city where it all went down.

In a cinematic gesture of reckoning and redemption, she listens as they set the record straight — and lay their burden down.

Can we make peace with the past? What lessons have we learned? What really happened up there on the 9th floor?

It started quietly when a group of Caribbean students, strangers in a cold new land, began to suspect their professor of racism.

It ended in the most explosive student uprising Canada had ever known.

Over four decades later, Ninth Floor reopens the file on the Sir George Williams Riot – a watershed moment in Canadian race relations and one of the most contested episodes in the nation’s history.

It was the late 60s, change was in the air, and a restless new generation was claiming its place – but nobody at Sir George Williams University would foresee the chaos to come.

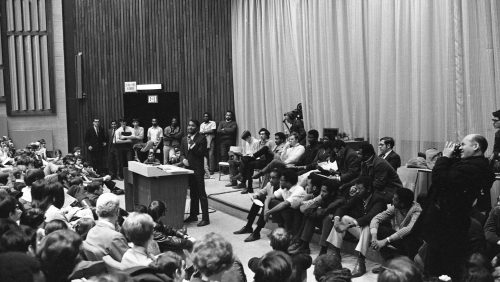

On February 11, 1969, riot police stormed the occupied floors of the main building, making multiple arrests. As fire consumed the 9th floor computer centre, a torrent of debris rained onto counter-protesters chanting racist slogans – and scores of young lives were thrown into turmoil.

Making a sophisticated and audacious foray into meta-documentary, writer and director Mina Shum meets the original protagonists in clandestine locations throughout Trinidad and Montreal, the wintry city where it all went down. And she listens.

Can we hope to make peace with such a painful past? What lessons have we learned? What really happened on the 9th floor?

In a cinematic gesture of redemption and reckoning, Shum attends as her subjects set the record straight – and lay their burden down.

Cinematography by John Price evokes a taut sense of subterfuge and paranoia, while a spacious soundscape by Miguel Nunes and Brent Belke echoes with the lonely sound of the coldest wind in the world.

Promotional Materials

Trailer

A conversation with director and writer Mina Shum

How did this story come to you?

The producer, Selwyn Jacob, and I met about the project in 2011. He’d been wanting to make a film about Sir George Williams ever since the events happened in 1969, and had done a lot of research over the years. He was a university student at the time in Alberta and it was big news on campuses across the country. And he’s from Trinidad, so he felt personally connected to the Sir George students. After our meeting, my first response was: this is a feature film! I was intrigued, and we started developing it together.

But I needed a point of entry. What made this a movie I had to make? Beyond the hard facts, who are these characters and why should I tell this story? I went to Montreal, where I interviewed some potential subjects – Clarence Bayne, Nantali Indongo and Marvin Coleby – and spent time in the archives.

It was when I came across the words “charges of racism” that I got hooked. It was shocking to see it stated, all raw like that. It made me think of how I deal with racism in my own life. And then I learned that our subjects were all under surveillance at the time: they were being watched. I’ve always wanted to make a spy movie. So here were these elements, the watcher and the watched, coupled with my personal emotional response, and it got me very excited from a filmmaking perspective.

Did you know about the Sir George Williams Affair before you made the film?

Not at all, and that was further motivation for me to make the film. At one point during research I interviewed Leroy Butcher, who has since died. He was a student leader at the time and said to me “This is a national story; it is a hidden story.” That bothered me: why hasn’t this been told?

Then I spoke to Rodney John, one of the students who lodged the first complaint of racism. He went on to become a psychologist, and we talked about the idea of suppression: if you, or a society, suppress feelings or thoughts, they will manifest themselves later in the physical world. It’s Carl Jung who said that and it’s something I think about a lot as a storyteller. How are the Sir George events a physical manifestation of something we’re suppressing?

Rodney also talked about fear and how it feeds itself – and how a sense of fear on all sides propelled the conflict forward. That became another point of entry, because that’s something everyone can change. The film needed a reason to exist, beyond history, and I’ve always been interested in what it means to feel fear, to be judged. And how our actions can reverberate.

As I got deeper into the historical material, I began to develop this theory about Expo 67. It was such an important moment for Montreal and for Canada. It made this grand promise of diversity, the idea that Canada was a welcoming place. Lots of immigrants, from the Caribbean and elsewhere, came to Canada in those years. My own family came from Hong Kong during this time. In a pivotal way, it was Expo that set the scene for the events that went down at Sir George Williams.

How did you decide upon the film’s structure and tone?

I had a clear idea from the start of how the film should unfold. I knew it would be propelled by the characters, by the idea of the resilient human spirit. And I always wanted it to be a hopeful film, despite the trauma and the pain.

We set out to do something different with the interviews. I’d been doing gallery installation and theatre work where I’d been interviewing real people in a poetic way, and I wanted to bring that approach to the film. So we did lots of work on that front, finding the right locations and designing shots that broke away from traditional documentary set-ups.

When it came to conducting the interviews, I saw myself as a kind of confessor rather than an investigator. I wasn’t interested in journalistic investigation so much as simply listening. I wanted to help the subjects set their story down. So the film became a collective effort. We trusted each other, and we made it together. We ALL got to walk around in the freezing Montreal winter, and to feel what it’s like to be isolated and judged. I’m interested in the small changes we can all make in our individual perspectives.

The idea of highlighting the theme of surveillance was also there in the initial treatment. I love the films of Alan Pakula, and those stylish thrillers from the 70s. And this project came to me at a perfect time, because I’d been thinking about surveillance.

When it came to the editing, we telescoped some of the historical facts. There were so many fumbles on the part of the university administration, and my editor Carmen Pollard and I did a lot of reorganizing. We needed to keep essential information, but we wanted to keep it compelling and entertaining. It’s important that the film be dramatic, emotional, cinematic but with a strong narrative line.

How did your experience with feature fiction come into play?

I planned the shoot as if it was a feature. I actually wrote whole scenes, with specific props and sets in mind. And we scheduled the shoot like a fictional film, with real people as actors. I put costumes on them, I gave them props, and I worked with DP John Price and our awesome production designer Elizabeth Williams to determine the colour palette. Those 70s thrillers were a reference point for the look I was going for.

We wanted the film to have a definite aesthetic and look, to conjure up this bleak world of wintry Montreal, with its modernist architecture. Like the loneliest heartbreak. The city itself provided lots of inspiration – the metro, the Expo site, and the Hall Building itself, where it all went down.

Every scene was shot listed. There’s one complicated sequence where we put Nantali Indongo, Rodney John and Robert Hubscher at different spots in the Bonaventure metro station, and it required the same kind of coordination and teamwork that you need on a feature shoot.

I wanted this film to have an epic quality, to do the story justice.

Why Bob Marley’s Redemption Song?

“None but ourselves can free our minds.” I love that idea. That line is why the song is in the movie. I’d incorporated it into my first script. It ties in with the whole theme of making peace with all the pain. Am I going to carry the narrative of my pain and my scars – or am I going to put my burden down? That is our choice. You can look towards the light – or you can look towards the darkness.

Anyone who’s ever felt rejected will carry a scar. You have to choose to heal. At one point, while we were filming in Trinidad, Hugo Ford paused and said: “Making this film is good. I finally feel like I have more space in my head and heart.”

Another time, we were on Île Sainte-Hélène in the middle of winter, shooting a scene with Rodney John. I was about to send him out into the cold with a suitcase, and he turned and said: “I just want to thank you for this.” I got a powerful sense that participating in the film was cathartic for him in some way.

We were so fortunate to get Nantali Indongo and her group Nomadic Massive to perform it. That scene is a highlight for me. She, too, has carried the burden. Her father was Kennedy Frederick, who was at the forefront of the protest. He was deeply traumatized by the events, and has never really recovered from the treatment he received at the hands of the police and society in general at that time, so it’s fitting that his daughter is part of the film.

Tell us about your team

Even before we started shooting, I got invaluable help from Elizabeth Klinck, who’s one of the best visual researchers in the business. She unearthed vital archival footage. Caroline Sigouin and her team at the Concordia archives were also wonderful on that front. They got behind the project, and helped us track down some previously unseen material that brought a whole new dimension to the story.

John Price, the DP on the project, was brilliant. At one point, before we started shooting, he turned to me and said: “Ok, I’ve got one question. Who are the subjects talking to?” It was a totally basic question, but it really helped crystallize the vision. We talked a lot about perspectives, snow, and concrete.

Dan Emery, our production manager, was integral, and so was Roman Martyn, our location manager. Roman got us access to all kinds of remarkable Montreal locations, including Habitat, which turned out to be a key site. He has a very calming demeanor and effortless charm; a perfect combination when you’re trying to get people to open their doors for you.

Carmen Pollard was my editor and engaged sensitively with the material and the themes. She channeled the vision with care and tenacity. I’m so grateful.

The composer on the film is Brent Belke and nobody writes beautiful and sad better than him. He’s also a former punk rocker who spent a couple of decades in punk band SNFU, so he’s able to tap into the spirit of protest. And Miguel Nunes created this poetic and evocative sound design. He spent his childhood in Montreal, and you can feel the cold wind in his work.

There are a lot of other people who I consider part of the team, but I’ll spend this moment talking about Selwyn Jacob, the producer. His quiet, determined intelligence was essential. I loved that he’s a doc guy who loves Hitchcock and Truffaut. In making this film, he was totally into the flow of fiction and doc.

What does it mean to make this film with the NFB?

I don’t think there would be this film without the NFB. Without the NFB these questions of how we see each other and how we treat each other would never be on the table.

A conversation with producer Selwyn Jacob

What are your personal memories of 1969 and the Sir George Williams Affair?

I remember it well. I was a recent immigrant from the Caribbean myself. I’d just arrived in Canada, and was studying at the University of Alberta at the time.

I learned about the events in a curious way, through one of my professors in Edmonton. I’d invited him to various Caribbean student events, and we’d become good friends. Then one morning, he turned to me in class and said, “Well, I hope we’re still friends.” I was puzzled by the remark, and it was only later, when I heard the news from Montreal, that I understood where his comment was coming from.

So I’ve always felt a direct connection to the story. A number of friends from my home village in Trinidad were studying at Sir George Williams at the time, and I could easily have ended up there myself. I’ve been hooked from the beginning, and I’ve been quietly collecting information on the event for decades.

How did you bring the story to the screen?

I’ve wanted to make this film ever since I became a filmmaker. At first, it was because of my own associations with the story, but as time went on I realized that the story could have resonance for all Canadians.

Then five years ago, at one of our programming meetings in the Pacific & Yukon Studio, I raised the idea again. At the time we were considering a film adaption of a new book about 1968, and it occurred to me that the Sir George Williams Affair was an interesting prism through which to look at that period in Canadian history. I was busy working on Mighty Jerome at the time, but I started researching the project in earnest.

Mina Shum came to the project a little later. The NFB had wanted to work with her for some time, and then we crossed paths at the Whistler Film Festival, where she was sitting on the documentary jury. She wasn’t familiar with the history, but I gave her the basic facts, and she was immediately interested. We began a long a fruitful conversation about what kind of film it could be.

How has Mina Shum approached the material?

She’s brought style and compassion to the project. She’s found an original way of putting it onscreen, drawing upon her own immigrant background and her extensive experience as a feature film director.

She began by researching the archives, looking for an original point of entry. We got great cooperation from the archivists at Concordia University’s Records Management and Archives. They helped us unearth some remarkable material, including footage that had been shot inside the university’s Hall Building at the height of the occupation. It was on an obsolete format, and had not been seen for decades, but once we managed to get it transferred, it provided vital new material for the editor.

Mina’s is a good listener: people want to tell her their stories. She was able to win the subjects’ trust, and to revisit a painful past that remains unresolved for many of them. She decided early on to avoid traditional recreations and obvious b-roll, and instead she interviewed people in stylized settings. She’s got a great sense of location, and we shot all over Montreal and Trinidad. In one winter sequence, we used Habitat, one of the buildings from Expo 67, and the effect is striking.

We know now that the student leaders were under pretty constant surveillance. They were being watched, and that fascinated Mina. She loves spy movies, and she makes intriguing references to the genre throughout the film, highlighting the uncertainty and paranoia that characterized the time.

Was it difficult to convince the surviving protagonists to participate?

Some subjects came on board immediately. They were more than willing to share their stories, but others took some convincing. They had all paid a huge price for the stand they took. They were taken to court, and some were deported. Their lives were completely derailed.

Some of them managed to move on and have happy and productive lives. They were a pretty remarkable group. Rosie Douglas, who was imprisoned and then deported, later became Prime Minister of Dominica. Anne Cools went on to become the first Black Canadian to be appointed to the Senate, and Rodney John has had a distinguished career as a psychologist.

But others never really recovered. Kennedy Frederick, one of the most fearless voices at the time, was deeply traumatized by the events. He features prominently in the archival footage, but he could not be interviewed for the film.

As fate would have it, Kennedy Frederick’s daughter Nantali Indongo still lives in Montreal. She’s an activist like her father, and also a musician. She is a member of a musical collective called Nomadic Massive, which makes a wonderful contribution to the film’s soundtrack.

What has changed in Canada since 1969?

There’s no doubt that racism persists. There’s still a lot of work to be done on that front. But Canadian society has evolved since 1969, and in many ways it’s a different country now. The fact that the National Film Board is producing this film – with Mina Shum as director and me as producer – is one important measure of how things have changed.

Key Events

- 1967: Expo 67, arguably the greatest world fair of the 20th century, puts Montreal and Canada in the world spotlight, projecting an inviting image of modernity and internationalism.

- February 1968: A small group of Caribbean students at Sir George Williams University – which later merges with Loyola to become Concordia – raises concerns about their biology lecturer Perry Anderson. They maintain he is discriminating against them and that his teaching is substandard.

- May 1, 1968: The students lodge an official complaint against Anderson with the Dean of Students Magnus Flynn.

- May 5, 1968: Representatives of the students meet with faculty to discuss their charges against Anderson.

- June 14, 1968: The administration rules that there is no evidence to support the students’ charge of racism, but acknowledge that teaching standards in Anderson’s class could be improved. A number of the students graduate and move on.

- Fall 1968: Dissatisfied with how the administration has handled their grievance, the original complainants resume their protest. They demand the formation of a hearing committee that includes student representation and mount a public campaign.

- October 11 to 14, 1968: Stokely Carmichael, a leading figure in the Black Power Movement, draws crowds when he speaks at the Black Writers Conference in Montreal

- October 1968: Inspired by the student uprising in Paris, Quebec students mount mass protests against inefficiency and inequity in Quebec’s education system.

- December 5, 1968: A group of students approach Principal Robert Rae in his office. They demand the dismissal of Perry Anderson. Rae refuses to do so without due process. Faculty agrees to form a five-member hearing committee that includes two Black professors.

- January 17, 1969: The committee sets January 26 as the first day of hearings.

- January 22, 1969: The two Black professors, Chester Davis and Clarence Bayne, resign from the committee. Three students, led by Kennedy Frederick, enter the office of Vice-Principal John O’Brien. They demand that O’Brien apologise for suggesting they pose a violent threat to Anderson. O’Brien signs a letter of apology but later lays charges of kidnapping and extortion again the three students.

- January 23, 1969: The complainants convene their own large meeting, drawing students and faculty. They refuse to accept the authority of the new hearing committee on the grounds that Davis and Bayne have been replaced without their input.

- January 26,1969: The new hearing committee holds its first official meeting. The complainants boycott the event and hold a counter meeting that draws support from other students.

- January 28, 1969: The editor of The Georgian, the student association newspaper, invites a group of Black students to edit a special issue. Copies are allegedly seized by the RCMP.

- January 29, 1969: In protest against the official hearing process, about 200 students occupy the university’s computer centre on the 9th floor of the Hall Building in downtown Montreal.

- February 7, 1969: The occupation extends to the faculty lounge on the 7th floor of the Hall Building.

- February 10, 1969: A tentative settlement is struck whereby the students agree to end their occupation if the administration establishes a more representative hearing committee and assists students who’ve fallen behind with coursework. The occupying students begin to leave the Hall Building. Less than 100 remain when they learn that the agreement has collapsed. They barricade the stairwells, and the administration calls for police intervention.

- February 11, 1969: Police storm the occupied floors of the Hall Building. A fire in the 9th floor computer centre causes extensive damage. The police arrest 97 people. Chaos ensues in the surrounding streets. The event makes headlines around the world.

- February 12, 1969: Perry Anderson is reinstated in his position.

- February 18, 1969: Preliminary trials of the arrested students begin. Various court cases relating to the February 11 events will continue for over five years.

- June 30, 1969: The Hearing Committee reports that nothing in the evidence substantiates a charge of racism against Anderson

- April 29, 1970: Protests take place Trinidad and elsewhere in the Caribbean, expressing solidarity with the arrested students.

- April 1971: Sir George Williams adopts its University Regulations on Rights and Responsibilities, providing for student representation on decision-making bodies. An Ombudsman Office is established.

- 1975: Roosevelt Douglas, one of the student leaders, is deported to his native Dominica having served an 18-month jail sentence on charges relating to February 11. In 2000 he is elected Prime Minister of the Caribbean island nation. Later that year he accepts an invitation from the Concordia Student Union to speak on campus.

- 1984: Anne Cools, who served a four-month sentence for her involvement in the February 11 events, becomes the first Black Canadian to be appointed to the Canadian Senate.

Subjects

Duff Anderson

Duff Anderson is the son of Perry Anderson, and the second of five of Perry’s children. He describes growing up in a liberal-minded home. Only five years old at the time that his father was accused of racism, Duff didn’t get to fully understand what had happened to his family until he read Dorothy Eber’s book: The Computer Centre Party.

Duff’s parents divorced, conceivably due to the stress of the events. He was raised by his paternal grandmother, father and stepmother and now lives and works in Montreal, Quebec.

Perry Anderson

By age 29, Perry Anderson was a father of five and an accomplished biology professor working on his PhD. Accused of systematically failing Black students, this young professor was eventually suspended. He was exonerated by an independent tribunal and returned to teaching briefly at Sir George Williams University.

Terrence Ballantyne

Born in Trinidad, Terrence Ballantyne came from a politicized family – his father was friends with C.L.R. James, whom Terrence considered a mentor. Terrence Ballantyne was preparing for medical school at Sir George Williams University during the time of the student protest. He was the president of the West Indian Society and one of the original complainants who laid charges of racism against professor Anderson.

Instrumental in helping to organize and plan meetings around the crisis, Ballantyne played an active role in the occupation, but was in the mezzanine (not on the 9th floor) when the fire broke out.

Terrence Ballantyne became a lawyer and returned to Trinidad where he continued his role as an activist.

Clarence Bayne

Clarence Bayne came from Trinidad to Canada in 1955. He obtained a BA and Master’s degree from UBC, and in 1977 he acquired a PhD in Economics from McGill.

In 1966, Bayne was hired full-time to teach statistics at Sir George Williams University. He was one of the original hearing committee members, which was formed to examine the students’ allegations against professor Anderson. After much pushback from the Caribbean students, Bayne quickly resigned. He felt that he could not be the judge and the jury at the same time.

Clarence Bayne continues to teach at the John Molson School of Business at Concordia University. He serves as Director for the Institute for Community Entrepreneurship and Development and is the Co-founder of the Quebec Black Board of Educators, the Black Study Centre, Black Theatre Workshop, and Canada’s first attempt at a national Black organization, the National Black Coalition of Canada.

Valerie Belgrave

Valerie Belgrave was born in San Juan, Trinidad. Her father had formerly studied at McGill University and moved the family back to Canada for their education. Belgrave chose Sir George over McGill for the Fine Arts program.

Belgrave joined the student protests and played an active role in the cleanup committee on the 9th floor. She was charged on five counts of arson and conspiracy. She later helped raise bail for Kennedy Frederick.

Belgrave did eventually graduate with a Fine Arts degree from Concordia University. She returned to Trinidad, is a published author and a well-known Batik Artist.

Mark Chang

Mark Chang is a Chinese Caribbean from Trinidad. He worked at the Expo 67 Trinidad and Tobago Pavilion. He was in his senior year for a Bachelor of Commerce degree and treasurer of the Caribbean Student Society when he joined the occupation.

Chang returned to Trinidad where he currently resides.

Marvin Coleby

Marvin Coleby was born in Paris and raised in the Bahamas. He became a student at Concordia in 2008 and is currently a graduate student in law at McGill University. Coleby learned about the events of 1969 while he was president of the Concordia Caribbean Student Union.

Senator Anne Cools

Senator Anne Cools was born in Barbados in the 1940s and moved to Montreal at thirteen years of age. During the 1960s, she was a key member of the Caribbean Conference Committee and the C.L.R. James Study Circle. At the time of the Sir George Affair, Cools was a McGill student studying sociology and psychology. In solidarity, she joined the student protest, providing a strong female voice to an already outspoken group.

Cools was arrested and jailed for her participation in the occupation. She refused to plead guilty and was sentenced to four months in prison.

Anne Cools went on to become an active feminist – establishing one of Canada’s first women’s shelters, Women in Transition Inc., in 1974. In 1984, she was summoned to the Canadian Senate by then Governor General Edward Schreyer, on the recommendation of Pierre Trudeau. There, she became the first Black senator in Canada, and the first Black female senator in North America.

Rosie Douglas

Rosie Douglas was the second eldest of 16 children. He came from a well-off family – his father having been a rich landowner who made his money in Curacao’s oil fields. Douglas began his colonial education in Roseau before coming to Canada to continue his studies at Ontario Agricultural College, Sir George Williams University, and finally McGill University.

It was in Montreal that Douglas experienced racism for the first time. He quickly became influenced by Martin Luther King and various other Black Power leaders, including Stokely Carmichael. Douglas was already a post-graduate student from McGill during the time of the Sir George Affair. He joined the protest and was eventually charged with arson, serving 18 months in prison. Douglas was considered a threat to Canadian National Security and was deported to Dominica. He developed a balancing act of participation both in domestic and world politics.

In 2000, Rosie Douglas became prime minister of Dominica, but died soon after at the age of 58.

Hugo Ford

Hugo Ford grew up in Trinidad. He moved to Montreal in his early 20s to study. Known then as Obu (meaning “rock”), Ford was committed to the entire two-week occupation. He was severely beaten upon arrest, imprisoned for a short time at Parthenais, and fined approximately $13,000.

Ford left Montreal right after the hearing, returning to Trinidad in 1973. He then came back to Montreal in 1976 to finish a degree in Applied Social Science before finally settling in Trinidad in 1980.

Ford is a father, a landowner, gardener and beekeeper. He believes in living a simple life and enjoys the physical labour of working the land.

Kennedy Frederick

From Grenada, Kennedy Frederick (not interviewed in the film) was one of the original six complainants. He was first charged with extortion and unlawful confinement and then arrested after the fire broke out.

Frederick escaped to Tanzania immediately after receiving bail. He currently resides in Grenada and struggles with his mental health.

Robert Hubsher

Robert Hubsher was a second-year psychology student at Sir George in 1969. He too came from an immigrant family, of Jewish descent. Hubsher became one of the key white students to participate in the protest after witnessing the debacle in room H110. He joined the occupation, was arrested after the fire broke out and jailed for six days.

Hubsher is the Executive Director of the Ramapo Catskill Library System in New York City.

Naim Indongo-Bangoura

Naim Indongo-Bangoura is Nantali Indongo’s son. His presence in the film serves to remind us of the very real racism and ensuing social issues that Black Canadians still face today.

Nantali Indongo

Daughter of the legendary Kennedy Frederick, Nantali Indongo feels that she has inherited both the benefits and the pain associated with the Sir George Affair.

She is an activist and hip hop musician, sings in the popular hip hop group Nomadic Massive, and is co-founder of the education program “Hip Hop No Pop” which tours high schools and college campuses, teaching workshops on youth issues, including the non-violent origins of hip hop, and hip hop as a tool for social change.

Nantali resides in Montreal with her partner and their son Naim.

Rodney John

Rodney John was born in St. Vincent, West Indies. He arrived in Montreal in 1965, working as a domestic servant before becoming a porter at Expo 67. John was involved in progressive politics from 1966 onward, heavily influenced by events such as the Black Writers Conference.

John was a student at Sir George Williams University and one of the original six who launched the complaint against professor Anderson. He played an active role in the 9th floor sit-in, but was outside of the university when the fire broke out.

Rodney John’s involvement with Sir George changed his life direction; he decided not to go into medicine, but did go on to attain a PhD in Psychology, as well as an LLM in Dispute Resolution. For the past 23 years he has been working predominantly as a mediator. He currently works and lives in Toronto.

Noel Lyon

Noel Lyon served as Perry Anderson’s lawyer during the Sir George Affair. He is described as being very sensitive to the issue of racism, and was critical of the administration’s handling of the complainants.

Much of his adult life has been dedicated to working with Indigenous peoples in Canada. Today, Lyon is an Emeritus professor of Queen’s University and the author of Inside Law School: Two Dialogues about Legal Education (1999).

Lynne Murray

Lynne Murray was born in Montreal and grew up on the south shore where she experienced racism throughout her childhood. She worked as a hostess at Expo 67. Lynne was a student protester at Sir George; she too was arrested and jailed for her participation in the riot.

Lynne graduated from McGill University and, in the mid-80s, moved to Trinidad.

Claude-Armand Sheppard

A Defense attorney, Claude-Armand Sheppard was called on by the university to help intervene in the occupation and act as a witness on behalf of the university, ensuring that there was no police violence. He was asked to accompany the riot squad in the dismantling of the student barricade.

Currently, Sheppard practices Mediation and Arbitration Litigation in Quebec.

Bukka Rennie

Bukka Rennie left Trinidad in 1965 in search of opportunity. He became one of the organizers of the Montreal Congress of Black Writers, attended Sir George Williams University and played an active role in the Sir George Williams Affair. Rennie was tried for his role as one of the “Trinidad Ten” involved in the occupation.

He later co-founded Uhuru, a radical political organization centered on the principles of Pan-Africanism. In the 1970s, he co-founded the New Beginning movement (a Pan-Caribbean political organization). Rennie works as a journalist in Trinidad.

Team

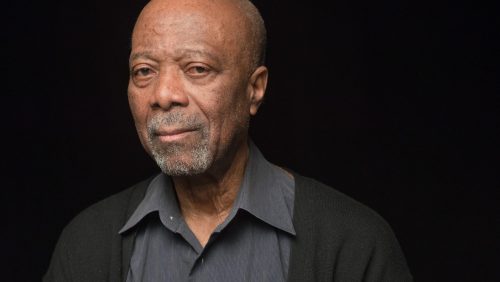

Mina Shum

Director

Photo

Photo : Véro Boncompagni

Selwyn Jacob

Producer

Photo

Photo : NFB

Images

Loading...

Photo: Marlon James

Photo: Marlon James

Download

Loading...

Photo: Marlon James

Photo: Marlon James

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Marlon James

Photo: Marlon James

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Photo: Vero Boncompagni

Download

Loading...

Photo: Paul-Henri Talbot

Photo: Paul-Henri Talbot

Download

Loading...

Photo: André Hébert

Photo: André Hébert

Download

Credits

Written and Directed by

Mina Shum

Producer

Selwyn Jacob

Editor

Carmen Pollard

Director of Photography

John Price

Composer

Brent Belke

Sound Designer

Miguel Nunes

Production Designer

Elisabeth Williams

Donna Mary Noonan

Location Manager

Roman Martyn

Etienne Desrosiers

Assistant Location Manager

Diane Janna

Production Manager

Dan Emery

Jennifer Roworth

Production Fixer

Princess Simone Donelan -Trinidad

Sound Recordist

Marco Fania

Gabor Vadnay

1st Assistant Camera

Carla Clarke

Martine Leclerc

2nd Assistant Camera

Camille Baduraux

Ann Berrie

Key Grip

Pierre Malouin

Bob McKenna

Robin Pishton -Trinidad

Best Boy

Sylvain Bélanger

Chris Kralik

François Warot

Gaffer

Walter Klymkiw

Gaetan St-Onge

Éric Babin

Jean-Roger Ledoux

Iscah Straker -Trinidad

Data Management Technician

Sean Sweeney

Leon Rivers-Moore

Assistant Production Designer

Geneviève Burke

Props Designer

Alexander Sergejewski

Frank Seales –Trinidad

Props Production Assistant

Christopher Vadnay

Scenic Painter

Alain Clouatre

Sylvain Gauthier

Geneviève Reneault

Melanie Schmitz

Derek Tyrrell

Frank Seales -Trinidad

Production Assistant

Alexandre Cadieux

Camerin Cobb

Michael Harris

Guillaume Labrecque

Isabelle Limoges

Jessica Lee

Carliena Holder -Trinidad

Creative Director –Graphics

Carmen Pollard

Visual Effects Artist

Brett Keyes

Graphics Illustrator

Brock Ellis

Archival Research

Elizabeth Klinck

Tom Puchniak

Lesley-Anne Macfarlane

Research

David Austin

Transcription

Tracy Sitter

Archival Materials

CBC Archive Sales

Archives Radio-Canada

CBC Licensing

CTV News Stox, a division of Bell Media Inc.

NFB Images

Records Management and Archives, Concordia University

Stock footage courtesy, The WPA Film Library

Getty Images

ITN Source

ITN Source/Reuters

Archival Materials

AP Images

Corbis

Paul-Henri Talbot – La Presse

André Hébert – La Presse

Agence Québec Presse – Réjean Meloche

© 1976, Réjean Meloche

“Students going off to jail”

George Bird, Montreal Star, Feb. 13, 1969

“Professor Perry Anderson”

Morris Edwards, Montreal Star, Feb. 15, 1969

Senator Anne C. Cools – Senate of Canada

Archival Materials

Len Sidaway, Aussie Whiting and Eddie Collister, The Gazette©1969

Montreal Gazette, a division of Postmedia Network Inc.

photos by Apoesho Mutope

Used with the permission of the Trinidad Express

Used with the permission of the Trinidad Guardian

Music

Redemption Song

Written by Bob Marley

Published by Blue Mountain Music Ltd/

Irish Town Songs (ASCAP)

o/b/o Fifty-Six Hope Road Music Ltd. &

Blackwell Fuller Music Publishing LLC

Redemption Song

Performed by Nomadic Massive

Musicians

Alejandro Sepulveda, Nicolas Palacios-Hardy

Diegal Leger

Vocalists

Nantali Indongo,Louis Dufieux,Meryem Saci

Robintz Paul, Ralph Joseph

Nah Murderah

Composed by Nicolas Palacious-Hardy, Diegal Leger,

Alejandro Sepulveda, Vincent Stephen-Ong, Jason Selman,

Lyrics by Nantali Indongo, Louis Dufieux, Robintz Paul, Ralph Joseph, Meryem Saci,

Performed by Nomadic Massive, Courtesy of Nomadic Massive Productions, 2013. All rights reserved

Hey Friend Say Friend

Written & Composed by Stéphane Venne, Marcel Stellman

Productions Jacqueline Vézina enr.

Performed by Donald Lautrec, Arranged by Pierre Nolés

Courtesy of Disques Mérite

Sodrac

Stills Photographer

Vero Boncompagni

Jonathan Wenk

Marlon James -Trinidad

Voice Over

Mackenzie Gray

Original Music

Vince Renaud Score Mixer

Paul Forgues Music Engineer

recorded at The Warehouse Studio, Vancouver

Musicians

Mark Ferris, Cam Wilson, Marcus Takizawa.

Finn Manniche

Sound Editorial Services provided by

Bionic Audio

Miguel Nunes

Assistant Sound Editor

Simon Cho

Foley Artists

Don Harrison, Ian Mackie

Foley Recordist –

Rick “Smokey” Senechal

On-line Editor

Serge Verreault

Re-Recording Mixer

Jean-Paul Vialard

Music Recording

Geoffrey Mitchell

Digital Editing Technician

Isabelle Painchaud

Patrick Trahan

Pierre Dupont

Technical Coordinator

Steve Hallé

Associate Producer

Teri Snelgrove

Production Coordinator

Karen Downing

Kathleen Jayme

Technical Edit Coordinator

Wes Machnikowski

Production Supervisor

Kathryn Lynch

Marketing Manager

Leslie Stafford

Publicist

Patricia Dillon-Moore

Program Administrator

Jennifer Roworth

Executive Producer

Shirley Vercruysse

Media Relations

-

About the NFB

Founded in 1939, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) is a one-of-a-kind producer, co-producer and distributor of engaging, relevant and innovative documentary and animated films. As a talent incubator, it is one of the world’s leading creative centres. The NFB has enabled Canadians to tell and hear each other’s stories for over eight decades, and its films are a reliable and accessible educational resource. The NFB is also recognized around the world for its expertise in preservation and conservation, and for its rich and vibrant collection of works, which form a pillar of Canada’s cultural heritage. To date, the NFB has produced more than 14,000 works, 7,000 of which can be streamed free of charge at nfb.ca. The NFB and its productions and co-productions have earned over 7,000 awards, including 11 Oscars and an Honorary Academy Award for overall excellence in cinema.