Labrecque From Film to Memory

Michel La Veaux

2017

| 94 min

Selections and Awards

Official Competition36e Festival du cinéma international en Abitibi-Témiscamingue

Audience Prize for Best Documentary Festival de cinéma québécois des grands lacs à Biscarrosse

Best Film History Film AwardPessac Historical International Film Festival 2018

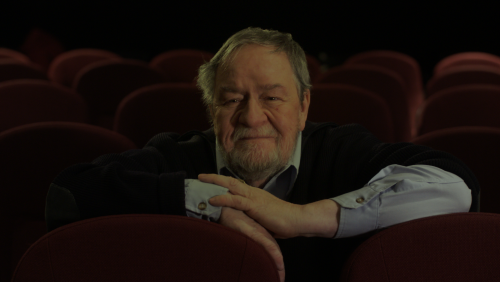

Michel La Veaux (Hôtel La Louisiane), a man who describes himself as being “passionate about light,” wanted to share his love of movie making with one of the pioneers of Quebec cinema: Jean-Claude Labrecque (À hauteur d’homme). At once a a respectful tribute and a touching portrait, Labrecque From Film to Memory plays out like a conversation between two friends.

While Jean-Claude Labrecque needed no coaxing to agree to be interviewed, Michel La Veaux, for his part, conveyed his love of cinema and affection for this modest giant not merely through words, but also through images. The palpably intimate discussion between Labrecque and La Veaux brings pages of Quebec cinema’s history to life and evokes the excitement of an era when such figures as Perrault, Brault, Jutra, Groulx, and Carle were brilliantly paving the way for future filmmakers.

Whether he is shooting documentaries or fiction, Michel La Veaux’s goal is first and foremost to make movies. This exceptional cinematographer and director, whose work on Sébastien Pilote’s dazzling second feature film, Le démantèlement (The Auction), earned him a Jutra for best cinematography, would never entertain the idea of neglecting the quality of images or the cinematic language. This is especially true when it comes to getting film buffs of all ages to discover or rediscover a major figure in our cultural heritage.

As a self-described man with a “passion for light,” Michel La Veaux wanted to share his love of movie making with one of the pioneers of Quebec cinema, someone he still considers a role model and inspiration: filmmaker Jean-Claude Labrecque (Les vautours [The Vultures], La visite du général de Gaulle au Québec, La nuit de la poésie and À hauteur d’homme). At once a respectful tribute and a touching portrait, Labrecque From Film to Memory plays out like a conversation between two friends.

While Labrecque—an adept and prolific storyteller—needed no coaxing to agree to be interviewed, La Veaux, for his part, demonstrates ingenuity in his eagerness to transcend the genre. He conveys his love of cinema and affection for this modest giant not merely through words, but also through images, framing, and movement.

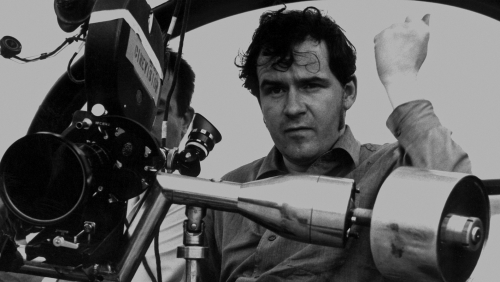

As in his previous feature documentary, Hôtel La Louisiane, in which this haven of freedom for artists and intellectuals appears in the opening shot in all its majesty, like a ship sailing in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, La Veaux does the same with Labrecque. He literally presents the venerable filmmaker as a monument in the memorable opening shot of Labrecque From Film to Memory.

Standing with his back to the river at the end of a dolly track, which La Veaux makes no attempt to conceal off-screen, Labrecque dispassionately stares at the camera as it slowly moves toward him until the shot culminates in a close-up of his face. Labrecque ceases to be a monument and once again becomes a man in the eyes of La Veaux, whose intention it was to shoot the images on a human level, in the manner of the humanist filmmaker.

In the low-key atmosphere of the Cinémathèque québécoise, the palpably intimate discussion between Labrecque and La Veaux, (the latter remaining discreetly hidden behind his camera), brings pieces of our history to life. It also evokes the excitement of an era when such figures as Perrault, Brault, Jutra, Groulx, and Carle were brilliantly paving the way for future filmmakers.

From the 40 or so works shot by Labrecque as a cinematographer or director, La Veaux selected a dozen, including Le chat dans le sac (The Cat in the Bag) by Gilles Groulx; La vie heureuse de Léopold Z (The Merry Life of Leopold Z) by Gilles Carle; and Labrecque’s Marie Uguay, a deeply moving portrait of the poet. La Veaux presents these excerpts in a way that produces a surprising double-mirroring effect: as Labrecque emotionally recalls the halcyon days when he took risks to create innovative, bold, never-before-seen images, La Veaux films those very images projected on a big screen. At the same time, he captures the projector’s hypnotic hum and then follows up with a visually sensual interplay between his camera and the projector.

Michel La Veaux and Jean-Claude Labrecque share the same passion for cinema as they do for cameras. When La Veaux invites Labrecque to Mel’s Studios, the almost carnal relationship they have with cameras is evident.

If we were to remember just one scene from this compassionate, moving, and fascinating documentary, it would unquestionably be the scene where La Veaux frames Labrecque in the centre of the Olympic Stadium. This is the very spot where Labrecque immortalized the 4 × 100-metre relay won by U.S. athletes in 1976 in Jeux de la XXIe olympiade (Games of the XXI Olympiad).

After performing the same camera movement with a vintage camera, Labrecque, seemingly energized by a quiet strength, looks straight ahead, as if to defy today’s filmmakers to dare to shake up our film industry the way he and other film pioneers have been doing since the 1960s. With Labrecque From Film to Memory, Michel La Veaux offers us a master class on cinema that is commensurate with this great man.

Interview with Michel La Veaux

What was the initial idea behind your second feature documentary, Labrecque, une caméra pour la mémoire / Labrecque From Film to Memory?

I wanted to make a cinematic film about one of our own great filmmakers, a founding figure of Quebec cinema, Jean-Claude Labrecque.

What do you mean by “cinematic film”?

I create documentary cinema. I don’t make documentaries. I’m not comfortable with being called a documentarian. I’m passionate about cinema . . . and about light. When I make a documentary, I need to do photographic research. I don’t make documentaries about social issues, like a documentarian, because that doesn’t interest me. There have to be images, the cinematic language has to be there. For me, documentaries and fiction represent the same challenge.

Images are all the more important when it comes to a film about a great director and cinematographer like Jean-Claude Labrecque.

I wanted to share my love of cinema with Jean-Claude and then show it to others, so I had to be creative. As was the case with my previous film, Hôtel La Louisiane, I’m in Labrecque, From Film to Memory but you can’t see me. You hear my voice—I actually rehearsed a lot with the sound editor, Olivier Calvert—and feel my presence and gaze through my choice of shots and camera movements. Instead of always using words to say that Labrecque is a great man, I say it with my camera.

Did you direct the film’s cinematography yourself?

Yes, as I did with Hôtel La Louisiane. And I asked Antoine Masson-MacLean to be my camera assistant again.

What does Jean-Claude Labrecque represent for you?

He’s a role model and an inspiration. I have immense respect and genuine affection for the man. In my view, Jean-Claude Labrecque was Gilles Groulx’s Raoul Coutard (Godard’s cinematographer). I think it’s important to remember that these people paved the way for us, that these great directors and cinematographers were bold. When you’re 18 and you’ve got Michel Brault and Jean-Claude Labrecque for inspiration, you’re really lucky!

Your documentary indirectly pays tribute to several filmmakers, including Groulx, who you just mentioned. Tell us about the relationship between Labrecque and the director of Le Chat dans le sac / The Cat in the Bag.

For me, Gilles Groulx is huge, but people have forgotten to what extent he was one of our great filmmakers. Actually, he’s the greatest, and I wanted to do him justice. Jean-Claude told me that if he’d continued to do cinematography for Groulx, he would never have become a director.

Jean-Claude Labrecque and Michel Brault inspired you when you were young, but who inspired Jean-Claude Labrecque in his youth?

Paul Vézina at the Office du film du Québec (OFQ–Quebec Film Board). I didn’t know him. Jean-Claude’s dream was to work with Brault, but he’s quick to say that Vézina was his mentor. Vézina’s the one who taught him about light. I like it when someone as great as Labrecque still admits he had a mentor.

The way you frame Labrecque in the opening shot makes it seem that you’re approaching him as if he were a monument.

I wanted to move toward Jean-Claude with my camera… use movement to approach him. In filmmaking, tracking shots produce the most beautiful movement. I wanted to include the dolly track in the field of vision, make it visible in the image. Jean-Claude is standing in front of the river. He’s at home, in Quebec City. On the water, a freighter is sailing out to the Atlantic. The tracking shot follows the freighter’s pace. I end that tracking shot with a close-up of Jean-Claude so that we see him on a human scale, the way he’s always looked at his subjects.

As in Labrecque’s work, tracking shots play a key role in your documentary.

Yes, tracking is the movement used in fiction movies that I apply to documentaries because my goal is to make documentary cinema. In my opinion, the scene at the Olympic Stadium is one of the most beautiful scenes in my film. I’d been wanting to set up that scene with Jean-Claude for a long time. He’s there, at the same place where he shot the 4 × 100-metre relay in 1976, in the same position, with the same camera, the old Éclair. The take he filmed in 1976 is projected on the stadium’s giant screen. I’m in a vehicle and move toward Jean-Claude with a tracking camera, ending with a close-up of him and his camera to show the magnitude of the man. And so I film the take from the Jeux de la XXIe olympiade / Games of the XXI Olympiad and merge it with the take that Jean-Claude is redoing.

Beyond the technical virtuosity, there’s also emotion in your documentary… even a certain solemnity.

Emotion is crucial to my work as a cinematographer and director. I always have an emotional relationship with light and framing, and naturally with the fictional or real characters. There’s a very simple shot that I really love, the one in the church where Jean-Claude is talking about Marie Uguay. I lit it like a fiction film, using movie lights from outside. Then I asked him to walk down the hill in the cemetery and look out at the river. We were on Île Perrot. I shot the scene once with the dolly track visible and once again without it visible. I kept the shot where the track can’t be seen so that, like in a fiction film, the filmmaking process wouldn’t be apparent in the image.

How many days did it take to shoot the entire movie?

In all, 11, including three days of interviews at the Cinémathèque québécoise. It’s very important to note that I got the films from the Cinémathèque. I chose 12 works out of about 50. I was able to count on the collaboration of film editor Nicolas Roy for choosing the excerpts. I always insisted on 35 mm on-screen projections because I didn’t want to show digital excerpts in my film. So I filmed the images from the screen. You can even hear the noise of the projector.

Incidentally, you have a very sensual way of framing that projector, as if you were caressing it with your camera…

I have a sensual love relationship with that equipment. I think it’s beautiful! Cameras are beautiful to me! When Jean-Claude says how much he loves the Arriflex S, I understand what he means: it’s the first camera I worked with. I love it as much as he does. And he didn’t know that. I love the harmony of shapes. A cinematographer is always looking for beauty. Actually, it doesn’t have to be beautiful, it just has to be accurate and meaningful. Those shots convey my love of cinema.

Speaking of cameras, you seize the opportunity to take us to a place that is not well known to the public.

Yes, the camera service at Mel’s Studios. That’s where I feel at home, where I’m the happiest in the world. No one knows the place, except cinematographers and camera assistants. For Jean-Claude, I had them bring out all the cameras he’d worked with.

We get the feeling throughout the film that there’s a real bond between you and Labrecque. Did you consider it important for this tribute to have that friendly, human dimension?

What pleases me most is the bond that I have with this man, and also that I succeeded in talking about filmmaking with him and made a cinematic film, even if it’s with a talking head. That being said, I don’t like the word “tribute.” Instead, I made it my moral obligation to remind the world that Jean-Claude Labrecque is a key player in Quebec culture. Quebec cinema is an important part of our culture. In my opinion, Quebec filmmakers are just as significant as writers and singers: we have to acknowledge them.

Trailer (in French only)

Images

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Team

Michel La Veaux

Director

Photo

Photo : Jasmina Parent

Nicole Hubert

Producer (ACPAV)

Photo

Photo : Katerine Giguère

NATHALIE CLOUTIER

Producer (NFB)

Photo

Photo : Sophie Quevillon

Jean-Claude Labrecque

Director

Photo

Credits

DIRECTION, RESEARCH AND SCRIPT

MICHEL LA VEAUX

ACPAV PRODUCERS

NICOLE HUBERT

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

BERNADETTE PAYEUR

NFB PRODUCERS

NATHALIE CLOUTIER

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

COLETTE LOUMÈDE

CINEMATOGRAPHY

MICHEL LA VEAUX

EDITING

NICOLAS ROY

ONLINE EDITOR AND COLOURIST

YANNICK CARRIER

SOUND DESIGN

OLIVIER CALVERT

ORIGINAL MUSIC

INSTITUT

ARNAUD DUMATIN

EMMANUEL MARIO

INSTRUMENTS & ARRANGEMENTS

ARNAUD DUMATIN

EMMANUEL MARIO

TRUMPET

GABRIELE BLANDINI

TROMBONE

GAETANO CARROZZO

TUBA

FABIO ORLANDO

BRASS RECORDING

STEFANO MANCA

A SUDESTUDIO LECCE – ITALY

LOCATION SOUND

THIERRY MORLAAS-LURBE

MARCEL CHOUINARD

SOUND DESIGN

OLIVIER CALVERT

ASSISTED BY

SAMUEL GAGNON-THIBODEAU

RE-RECORDING

JEAN PAUL VIALARD

GAFFERS / GRIPS

PIERRE BEAULIEU

MICHEL AHELO

GUILLAUME PELLETIER

DAVID GIASSON

CAMERA ASSISTANT

ANTOINE MASSON MAC LEAN

COORDINATOR

GINETTE LAVIGNE

ADMINISTRATOR

CLAUDETTE DUBÉ

MAKEUP ARTIST

KATHRYN CASAULT

NFB POST-PRODUCTION

TECHNICAL COORDINATOR

MIRA MAILHOT

TECHNICAL SUPPORT – EDITING

PIERRE DUPONT

ISABELLE PAINCHAUD

PATRICK TRAHAN

TITLES

MÉLANIE BOUCHARD

NARRATION RECORDING

GEOFFREY MITCHELL

PROJECTIONISTS

GUY FOURNIER

GLENN MARTIN

EDITING ASSISTANT

JORDAN VALIQUETTE

ARCHIVAL MATERIALS

STILL PHOTOS

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA

CINÉMATHÈQUE QUÉBÉCOISE

BIBLIOTHÈQUE ET ARCHIVES NATIONALES DU QUÉBEC

MARCEL CARRIÈRE

REAL FILION

FILM AND VIDEO

FILMS JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

RADIO-CANADA

NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA

MONIQUE SIMARD

FILM EXCERPTS

JOUR DE JUIN

NFB, 1959

UN JEU SI SIMPLE

GILLES GROULX

NFB, 1963

LE CHAT DANS LE SAC

GILLES GROULX

NFB, 1964

MÉMOIRE EN FÊTE

LÉONARD FOREST

NFB, 1964

GENEVIÈVE

MICHEL BRAULT

NFB, 1964

60 CYCLES

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

NFB, 1965

LA VIE HEUREUSE DE LÉOPOLD Z

GILLES CARLE

NFB, 1965

LA VISITE DU GÉNÉRAL DE GAULLE AU QUÉBEC

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

FILMS JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE ET NFB, 1967

L’HIVER EN FROID MINEUR

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

FILMS JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE, 1969

LA NUIT DE LA POÉSIE 1970

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

AND JEAN-PIERRE MASSE

NFB, 1970

ESSAI À LA MILLE

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

FILMS JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

1970

LES SMATTES

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

FILMS JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE, 1972

LES VAUTOURS

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

FILMS JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE, 1975

JEUX DE LA XXIE OLYMPIADE

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE,

GEORGES DUFAUX, JEAN BEAUDIN,

MARCEL CARRIÈRE

NFB, 1976

LA NUIT DE LA POÉSIE 28 MARS 1980

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

AND JEAN-PIERRE MASSE

NFB, 1980

MARIE UGUAY

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

NFB, 1982

LE RIN

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

LES PRODUCTIONS VIRAGE INC., 2002

À HAUTEUR D’HOMME

JEAN-CLAUDE LABRECQUE

LES PRODUCTIONS VIRAGE INC., 2003

LEGAL ADVISOR

VIVIANNE DE KINDER

NFB TEAM

LINE PRODUCER

MÉLANIE LASNIER

MARKETING MANAGERS

KARINE SEVIGNY

FRANÇOIS JACQUES

ASSISTED BY

FLORENT PREVELLE

JOLÈNE LESSARD

PRESS RELATIONS

NADINE VIAU

ADMINISTRATOR

SIA KOUKOULAS

PRODUCTION COORDINATOR

CHINDA PHOMMARINH

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

PASCALE SAVOIE-BRIDEAU

TRANSLATION AND SUBTITLES

CNST

RADIO-CANADA

SENIOR DIRECTOR, TV INFORMATION, FRENCH SERVICES

JEAN PELLETIER

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

GEORGES AMAR

PRODUCED BY

ACPAV

www.acpav.ca / membre AQPM

IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH

THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA

PRODUCED WITH THE FINANCIAL PARTICIPATION OF

WITH THE COLLABORATION OF

Media Relations

-

About ACPAV

For over 45 years, ACPAV has been developing and producing auteur films with a special emphasis on thought-provoking cinema. Directors and screenwriters whose work ACPAV has produced include Léa Pool, Mireille Dansereau, Paul Tana, Pierre Falardeau, Bernard Émond, Benoit Pilon, Sébastien Pilote, Sophie Deraspe and Richard Desjardins. ACPAV continues to develop new films and currently has projects by several new talents under way.

-

About the NFB

For more than 80 years, the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) has produced, distributed and preserved those stories, which now form a vast audiovisual collection—an important part of our cultural heritage that represents all Canadians.

To tell these stories, the NFB works with filmmakers of all ages and backgrounds, from across the country. It harnesses their creativity to produce relevant and groundbreaking content for curious, engaged and diverse audiences. The NFB also collaborates with industry experts to foster innovation in every aspect of storytelling, from formats to distribution models.

Every year, another 50 or so powerful new animated and documentary films are added to the NFB’s extensive collection of more than 14,000 titles, half of which are available to watch for free on nfb.ca.

Through its mandate, its stature and its productions, the NFB contributes to Canada’s cultural identity and is helping to build the Canada of tomorrow.