Embraced

Justine Vuylsteker

2018

| 5 min 24

Made using the Alexeïeff-Parker pinscreen

Selections and Awards

Best Classic Animation StyleLos Angeles Animation Festival- L.A.F.F. (2018)

Official SelectionAnnecy 2018

Official Selection - Canadian PanoramaOttawa International Animation Festival 2018

Competition - Short FilmsAnima Mundi International Animation Festival 2018

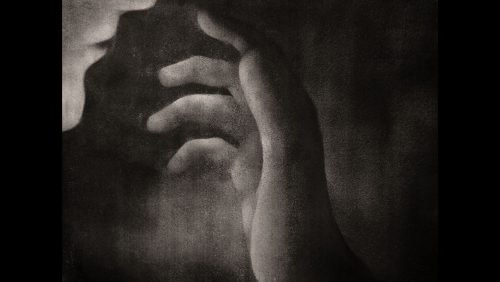

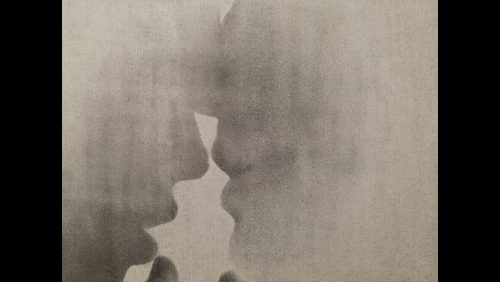

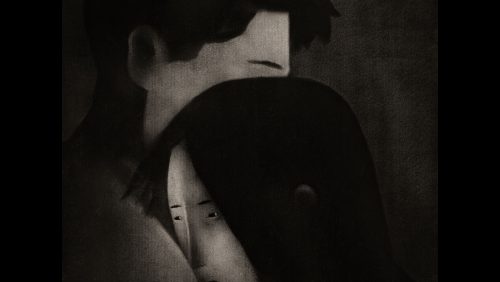

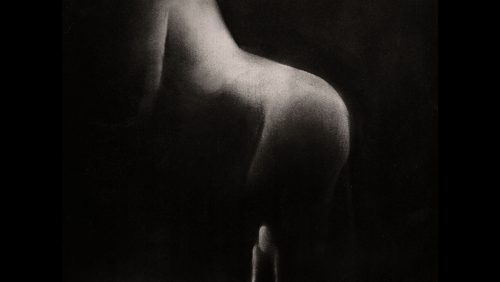

Standing before an open window, a woman gazes at black clouds darkening the horizon. She loves two men—the one who shares her present, and the one who marked her past. Frozen, she struggles against surging memories evoked by objects, the sky—everything. In the clouds, a passionately intertwined couple appears.

The first professional auteur short film by young French filmmaker Justine Vuylsteker, Embraced is a bittersweet visual poem that evokes fleeting sensations. With subtlety and sensuality, Vuylsteker reveals both the ruins of a relationship and traces of an intimate bond with an artistic process: the legendary pinscreen. Invented by Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker (Night on Bald Mountain), this animation technique has an eminent pedigree that includes being put to use by great NFB filmmakers such as Norman McLaren, Jacques Drouin and Michèle Lemieux.

Embraced, a coproduction of Offshore (France) and the NFB, is the first film made with “The Épinette,” owned by the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC) and the twin of the NFB’s own pinscreen. Vuylsteker has used it to express the passion of love and the dizzying struggle between remembrance and oblivion.

Standing before an open window, a woman gazes at black clouds darkening the horizon. She loves two men—the one who shares her present, and the one who marked her past. Frozen, she struggles against surging memories evoked by objects, the sky—everything. In the clouds, a passionately intertwined couple appears.

INTERVIEW WITH FILMMAKER JUSTINE VUYLSTEKER

When did you first become interested in the pinscreen?

When I saw the film Night on Bald Mountain, which I discovered early on at school, it left a really, really strong impression on me. So when I had to do an assignment on a specific animation technique for a first-year class, of course I chose the pinscreen! But even knowing its history and all the theoretical details, I still couldn’t figure out its workings. It remained very abstract! Some years later, when I saw the call for candidates for a pinscreen master class to be given by Michèle Lemieux, I put together an application right away. With Jean-Baptiste Garnero and Sophie Le Tétour of the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée, who are the two custodians of the Épinette (the French pinscreen), she chose eight filmmakers, and I was one of them.

How was it, learning the technique?

The master class was amazing. Michèle explained her vision of the pinscreen, but without ever imposing it on us. On the contrary, she encouraged us to make it our own. It was a very frustrating time, though, only three days—which meant each participant had very little “screen time” on their own. But I was at last able to grasp the connection between the images, the shadows, the light, the pins… The master class cleared up plenty of mysteries about the technique, and then it became obvious: I wanted to make a film with this material. Fortunately, we were then offered more time on the Épinette: each filmmaker was awarded a one-month development residency in Bois-d’Arcy, where the CNC archives are held. I was the first to jump at the opportunity!

Did you already have the basic idea for Embraced at that point?

I always keep a notebook with me, and take notes fairly compulsively, and already during the master class, I had written down this impression I had that the pinscreen was made to tell a love story. Because of how the tool embodies the dialogue between Alexeïeff and Parker, who worked together, one on each side of the screen—a man and a woman bound together by the tool they invented. It was like all I could see was this story of which the pinscreen was the fruit as well as the witness, and now continues to be the embodiment. I didn’t have a title or definite project, but the thought process had begun. At that point I wondered whether I should go in with a specific idea, to get the most out of my month with the screen, or if it was better to leave my mind as blank as possible, to see where that would take me…

So you decided to go with improvisation?

Partly! In a creative process, my natural tendency is control rather than abandon, and it was very tempting to arrive extremely prepared, with a clear idea in mind—but I managed to resist! Showing up neutral, I felt all the impressions that had been there during the master class suddenly wash over me: the tug-of-war between past and present, the conflict between love and desire, the silent dialogue of a couple conveyed through an object—the screen for Alexeïeff and Parker, a cup of tea in Embraced. During that month in Bois-d’Arcy, I didn’t do a single face: only bodies, clouds and a few movements. Then on the last day, when I had decided to simply clean the screen and reset it to black, a face appeared. And then another. It led to that twin portrait: a man and a woman. They crystallized everything that had gone before, lending form and a story to the impressions that I’d felt so strongly. The film was born at that moment.

How did you pursue the creative process after you no longer had access to the pinscreen?

After the residency, I took a year before doing any drawings for the film; all my work was in words. It seemed vital that I not erase the feelings I’d had working with the pinscreen. I wanted to hold on to what I had felt physically for as long as possible. If I had moved to another tool too fast, I think I might have lost the connection, somewhat, between subject and technique. Since there was no opportunity for me to go back (the other filmmakers each had their month-long residency as well), my construction and exploration were done through writing.

Writing seems to be a very important part of your approach. In addition to being a creator, you also write about the practice of animation filmmaking itself…

I’m very fond of literature, and I especially love reading authors who write about their craft. Fairly naturally, I wanted to read filmmakers or critics on the specifics of animation, but there’s hardly anything out there! My desire to write came in part from that frustration. There’s also the fact that public and critical discourse around animation is pretty disappointing, formulaic and not very relevant. I get the feeling that this inability to talk about it as specifically and with as much acuity as people do with live-action cinema comes from a feeling of not knowing how to talk about it. As if critics lack the keys or codes. They don’t dare take on the subject of animation; they’re often content to write about techniques, or admire the patience that’s required, completely forgetting to address the poetics of this cinema. But every art form needs vibrant, engaged criticism to maintain a healthy dynamics of questioning that provides impetus and enables innovation. The discourse around animation simply has to mature. And if critics aren’t able to tackle this imposing mountain that animation seems to represent, I think it’s up to the creators to make a move toward them and give them potential footholds, by providing them with words. Hence the need to write and to publish.

After nurturing your thinking about the film in writing, were you able to go back to the pinscreen directly?

My first route back was drawing. I created a very long notebook, a single drawing without interruptions, so that I could hold onto a measure of improvisation, of the unexpected, when the time came to shoot. The pinscreen is a tool that pushes you: there’s you and it, with no other intermediary. So you can afford yourself the possibility of improvising. The notebook was my form of preparation, because I can’t conceive of improvisation without extreme preparation: it’s only once you’ve perfectly assimilated the structure of the film that you can allow yourself to forget it. Because you know at that point that it will subconsciously guide all your choices and all your movements. With the notebook, I was able to set all my directions without actually deciding anything. And so many beautiful things happened during the actual shooting, when I was indeed able to let go, give up some control—that’s when the rain and the mist came in; all those aspects related to the elements, which I hadn’t written.

The result is a very open narrative, with more than one possible reading. Was this the case as early as the script stage?

It’s quite funny, the way in which my character gained her independence by the end of shooting. When you’re writing, you know a character’s intentions… and afterward, the film ends, and you don’t know any more! I’m really not sure any more if I know what happens for her. But the film that I wrote is the story of a love triangle. The two men belong to different eras, and the memory of her past relationship continues to pursue her in the present. But I’m really glad that the film allows for and triggers other interpretations, that viewers find enough room in it to project themselves into it and approach it differently. It was very important to me to create that space for freedom. Embraced is above all about the difficulty of being in the present. That state of being torn between memories and the present, of immobility, of apparent passivity although you’re trying to resist, and that past that returns without you having any say over it… That might be the thing that unites all the possible interpretations.

Is Embraced a melancholic film?

I see melancholy as an escape into the past that’s accepted—maintained, even—whereas in the film, she resists. She wants to be rooted in the present. Embraced seems to go beyond mere melancholy. There’s renunciation as well, courage, a certain idea of fidelity… and a lot of dignity, I think, in all these characters. So, yes, there is melancholy in the film, but it’s not only that. One of the things I love most about Embraced is that the film doesn’t seem comfortable to me, that every assumption you make about this woman’s story and her feelings leads to other ones. Why does she stay? Why does he stay? What keeps her from acting or forgetting? Why so much indecision? From the first reactions I got, it seems, to my great pleasure, that people don’t come out of the film expressing any clear sentiment—and that fits quite nicely with the moment this character is going through, where nothing is obvious.

Embraced seems to be a deep dive into the process of memory and forgetting.

It’s partly because of the pinscreen that I became aware of my interest in this question of memory. Surely because this tool seems to store inside it the memory of all the images created on its surface, and when you erase an image, it doesn’t disappear, but is absorbed by the screen and joins the sum total of all the past images. Nothing really dies; it’s there in the blackness of the shadows, not completely lost, but beyond our grasp, impalpable. In the screen’s way of resisting us, of evading us, of rejecting our intentions even, there is something very close to the whims of our memory.

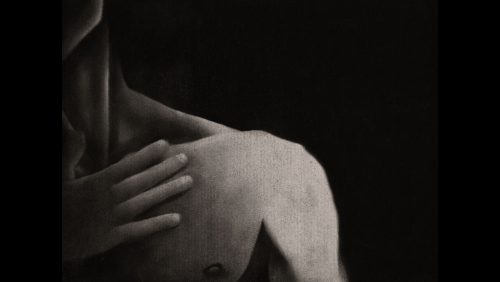

Your film also has this great sensuality, which seems to be directly connected to the technique you used.

The sensuality of the screen seems undeniable to me. Especially when you unveil its blank surface, when you disrobe it from its shadows, and you swear you can see skin. The tubes that hold the pins look uncannily like the pores of our skin… and when you heat up the screen to be able to manipulate it, the wax that holds the pins softens and is secreted by the tubes, like sweat. When you pull the pins slightly toward you, it’s almost like goosebumps appearing. The pinscreen is definitely very sensual! And the Épinette more so, perhaps, than the NFB screen, because its surface bears imperfections that the restoration couldn’t fix, like scars marking a body. And there’s the work posture, requiring extreme proximity between the screen and the person manipulating it, which means they must engage in something like an embrace.

Before Embraced, you made the animated film Fish Don’t Need Sex, which also depicts a union of bodies. Did you feel like you were making a series?

Yes, and it might end up a trilogy with my next film. To me, Fish is about the immediacy of that union, while Embraced shows the aftermath, the extension, the echoes of that moment even though it’s ended. Embraced is immersed in a feminine awareness, and I think the next one will adopt a masculine point of view. I started writing it a few weeks ago; it doesn’t have a clear trajectory yet, but I know I’ll be working with paper again.

Excerpt

Images

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

The Pinscreen: Description and Timeline

The pinscreen is a vertical screen with hundreds of thousands of perforations, each fitted with a retractable pin. Lit from the side, the pins cast shadows of varying lengths depending on how far they project out of the white screen. This grid of pins and shadows creates a grey-scale that ranges from black to white and is used to produce animated images with the look of engravings or charcoal drawings. The NFB’s pinscreen, currently the world’s only working model, consists of 240,000 pins in a 52 x 39 cm surface. Its slightly larger twin in France, dubbed the Épinette, has 277,000 pins extending over a 56.5 x 44 cm surface.

Timeline

1930

Artist and engraver Alexandre Alexeïeff creates a prototype “pinboard” to test his pinscreen concept.

1931

Alexeïeff starts building his first pinscreen, an apparatus made up of 500,000 pins with which he hopes to be able to make animated engravings.

1932

Backed financially by Claire Parker, a young American who had sought him out to learn about his engraving technique, Alexeïeff finishes building the first pinscreen.

1933

Together, Alexeïeff and Parker use the pinscreen to create Night on Bald Mountain, their masterpiece.

1935

Parker patents the pinscreen in Paris.

1941–1942

Living in Mount Vernon, New York, during the second World War, Alexeïeff and Parker build a pinscreen with 1,140,000 pins.

1944

While in Mount Vernon, they make En passant for the NFB, which commissioned the film to illustrate a popular song.

1961

The couple, now back in Paris, are visited by Norman McLaren who carries out a series of tests using the pinscreen; however, the tests lead to nothing further.

1963

Alexeïeff and Parker make their second great work, The Nose, after the short story by Nikolai Gogol.

1972

At McLaren’s instigation, the NFB acquires a pinscreen with 240,000 pins. Alexeïeff and Parker come to Montreal to hold an introductory workshop on using the device; animators Ryan Larkin and Caroline Leaf are among those who attend. The workshop is filmed by McLaren and Grant Munro; the footage will later be part of the educational documentary Pinscreen.

1974

Young filmmaker Jacques Drouin, who did not attend the Alexeïeff/Parker workshop, completes a first animated short using the pinscreen, Trois exercices sur l’écran d’épingles d’Alexeïeff.

1976

Drouin completes Mindscape. The film is applauded by the animation community, winning numerous awards and gaining the filmmaker tributes from Alexeïeff and Parker.

1980

Claire Parker dies.

1981

Alexandre Alexeïeff dies.

1986

Drouin and Bretislav Pojar complete Nightangel, which skilfully combines pinscreen animation with puppetry. As innovative as ever, Drouin also introduces colour to the pinscreen.

2004

Drouin continues his artistic research with Imprints, in which he explores the screen’s textures and contours.

2006

At the request of the NFB, Drouin gives a workshop on the pinscreen technique. Among the filmmakers in attendance is Michèle Lemieux.

2012

Lemieux completes Here and the Great Elsewhere.

2015:

Using the Épinette, Lemieux gives a three-day master class in pinscreen animation in Annecy. The workshop is followed by a month-long residency in Bois-d’Arcy, where the CNC maintains the Fonds Alexeïeff-Parker with the help of Jean-Baptiste Garnero and Sophie Le Tétour. Justine Vuylsteker is one of the eight participants.

2017:

Justine Vuylsteker spends time at the NFB and completes Étreintes, the first film made entirely on the Épinette.

The NFB and the Pinscreen

In 1944, the creators of the pinscreen—Alexandre Alexeïeff, a Russian-born artist living in France, and his wife Claire Parker, an American—made a short film for the NFB entitled En passant. Fast forward to 1961, when Norman McLaren, while visiting the couple on a trip to Paris, carried out a few tests using the apparatus. The tests led no further, but McLaren’s admiration for Alexeïeff prompted the NFB to acquire its own pinscreen in 1972. known as NeC (for nouvel écran, “new screen”) and made from 240,000 pins, this was the device on which animator Jacques Drouin would subsequently make all of his films, including Mindscape (1976). With Alexeïeff’s death in 1982, the NFB’s pinscreen became the world’s only working model. After Drouin retired, the NFB asked him to give a master class to share his unique skills with other artists. It was there that Michèle Lemieux first encountered the ingenious device on which she was to create Here and the Great Elsewhere, which she competed in 2012. That same year, France’s Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée (CNC) acquired the Épinette, the last pinscreen owned by Alexeïeff and Parker, and tasked Michèle Lemieux with restoring it to working condition. Three years later, in Annecy, Lemieux gave her own pinscreen master class, this time using the newly restored Épinette. The master class was followed by a month-long residency in Bois-d’Arcy, where Jean-Baptiste Garnero and Sophie Le Tétour are entrusted with the conservation of the Fonds Alexeïeff-Parker. Young filmmaker Justine Vuylsteker, one of the participants, learned the pinscreen technique and completed Embraced—the first film made entirely on the Épinette—at the NFB in 2017.

Promotional Materials

Team

Justine Vuylsteker

Director

Photo

Photo : Stéphan Ballard

Rafael Andrea Soatto

Producer (Offshore)

Photo

Julie Roy

Producer (NFB)

Photo

Photo : NFB

Credits

Script, Animation and Direction

Justine Vuylsteker

Offline Editing

Annie Jean

Additional Animation

Gilles Cuvelier

Sound Design

Olivier Calvert (ONF/NFB)

Original Score

Pierre Caillet

Violin

Éric Lacrouts

Cellist

Guillaume Martigné

Voice

Bruno Marcil

Technical Direction

Pierre Plouffe (ONF/NFB)

Technical Coordination – Animation

Yannick Grandmont (ONF/NFB)

Online Editing

Serge Verreault (ONF/NFB)

Titles

Mélanie Bouchard (ONF/NFB)

Foley

Lise Wedlock

Foley Assistant

Thomas Garant

Technical Coordination

Jean-François Laprise (ONF/NFB)

Sound Recording

Geoffrey Mitchell (ONF/NFB)

Re-recording

Jean Paul Vialard (ONF/NFB)

Production Coordination

Michèle Labelle (ONF/NFB)

Laëtitia Denis (Offshore)

Administration

Diane Régimbald (ONF/NFB)

Karine Desmeules (ONF/NFB)

Administrative Team

Diane Ayotte (ONF/NFB)

Stéphanie Lalonde (ONF/NFB)

Marketing

Geneviève Bérard ( ONF/NFB)

Assurance / Insurance

Gras Savoye

Bank

Martin Maurel

with the support of

Région Hauts-de-France

Ciclic – Région Centre-Val de Loire

This film received support through a residency at

Abbaye de Fontevraud

Cinémathèque québécoise

Producers

Rafael Andrea Soatto (Offshore)

Julie Roy (ONF/NFB)

Fabrice Préel-Cléach (Offshore)

Emmanuelle Latourrette (Offshore)

Co-produced by

Offshore

and the National Film Board of Canada

Offshore is a member of Syndicat des producteurs indépendants et d’UniFrance

visa no 146 350

© 2018 Offshore – National Film Board of Canada

To create this film, Justine Vuylsteker took part in an artist residency on creating and developing pinscreen projects, organized by the CNC at it Bois d’Arcy location.

The images in this film were made using the Alexeïeff-Parker pinscreen at the National Center for Cinema and Animated Image, which was made available free of charge.

Media Relations

-

About the NFB

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) is a leader in exploring animation as an artform, a storytelling medium and innovative content for emerging platforms. It produces trailblazing animated works both in its Montreal studios and across the country, and it works with many of the world’s leading creators on international co-productions. NFB productions have won more than 7,000 awards, including seven Oscars for NFB animation and seven grand prizes at the Annecy festival. To access this unique content, visit NFB.ca.