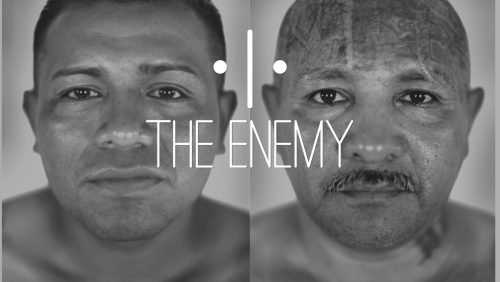

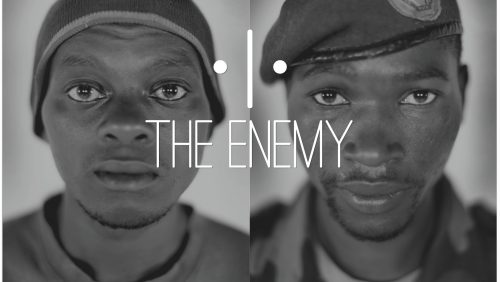

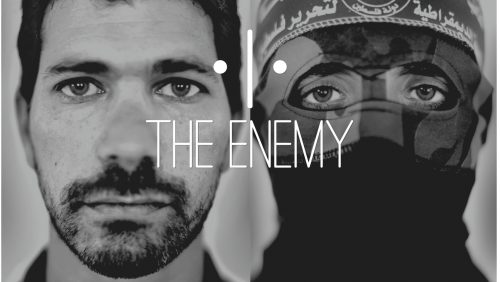

The Enemy

Karim Ben Khelifa

2017

| 60 min

Virtual and Augmented Reality

Selections and Awards

Winner - Most Illustrated Production on International NUMIX Awards 2019

CMF Grand PrizeNUMIX Awards 2018

Immersive Production Award - Cultural Production NUMIX Awards 2018

Journalism AwardWorld VR Forum 2018

SENSible AwardGeneva International Film Festival 2018

Best Virtual Reality ExperienceRose d'Or Awards 2017

Download the app now

Two-liner

An innovative, immersive experience in the heart of the planet’s longest-running conflicts, and at the intersection of virtual reality, neuroscience, artificial intelligence and storytelling.

The project

Two enemies stand face to face, observing each other.

In turn, each of them reveals the reasons behind their decision to go to war. How they came to take up arms to defend their values, their family, their tribe, or their faith—following in the footsteps of their parents and forebears who did the same.

What exactly do we know about these combatants? What do we really understand about the motives that push human beings to engage in combat—putting themselves at risk of both being killed and of becoming killers themselves? And why continue to fight over the course of several generations? What does freedom look like for these warriors? What is their future?

Israel and Palestine, Congo, El Salvador—of all the conflicts in the world today, these seem to be the ones that most dramatically represent the improbability of those on opposite sides ever identifying with one another.

For the past 15 years, war photographer Karim Ben Khelifa has been on an increasingly ambitious quest, driven by one question: What is the point of images of war if they don’t change people’s attitudes toward armed conflicts and violence and the suffering they produce? What is the point if they don’t change anyone’s mind? What is the point if they don’t help create peace?

The Enemy is a project that breaks away from the kinds of images of war the media typically shows us. By hearing the voices of those who carry this violence within them, by allowing them to introduce themselves and to share their motives and dreams, the project brings us face to face with these fighters and their points of view, humanizing them in the process. The Enemy doesn’t seek to provide answers or explanations; on the contrary, it attempts to share the experience of war and provoke discussion. The refusal to see an enemy’s humanity is defined not so much by the limits of empathy as by a lack of imagination—hence, one of the goals of The Enemy is to expand moral imagination.

The Enemy includes two interactive experiences:

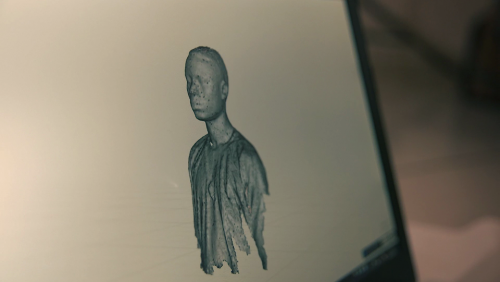

- The first is a face-to-face museum exhibit that makes use of virtual-reality headsets to place participants between these enemies, at the point where their gazes intersect. This cutting-edge installation brings together, for the first time, virtual reality and 3D reconstructions based on documentary material gathered in the field. The result is a unique and immersive experience.

- In addition, an application using augmented and mixed reality for smartphones will allow users to recreate the face-to-face experience in their own environments.

Fox Harrell, professor at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), also collaborated on the project’s design to put a whole new spin on the experience:

The script that plays out during the experience depends the user’s answers to a questionnaire, revealing any emotional bias he or she may have towards one of the three conflicts presented. The user’s behaviour, which is recorded throughout the installation, also determines which epilogue will be presented. Each visitor is unique; so is their experience with The Enemy.

Installation

A multiuser installation and global tour

In The Enemy, viewers will meet six combatants from three long-standing conflict zones: Israel-Palestine, Congo, and El Salvador. The virtual-reality exhibit supports up to 20 simultaneous visitors, but can be scaled up to accommodate more.

The exhibit integrates the latest advances in neuroscience to provide users with a personalized experience in which each person’s reactions affect the perceptions of others. By analyzing the personal processes that create empathy, the installation alters our virtual appearance so that we appear to the other players to be in the skin of a fighter.

In accordance with Karim’s wishes, this exhibit will also be installed in the conflict zones represented, so that younger generations can try the experience and perhaps alter their perceptions of the enemy—the “Other” they have experienced as dehumanized throughout their entire lives.

Application

The app: Another iteration of the project

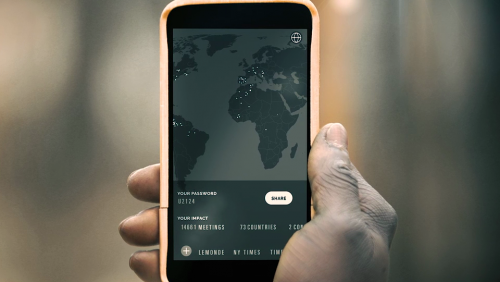

The Enemy is also an augmented-reality and mixed-reality app for iOS and Android mobile devices.

Users of The Enemy app get special access to the stories of six fighters emerging from the conflicts in Congo, El Salvador, Israel, and Palestine. Through augmented reality, users can explore these stories in their own environment. Prior to the encounter, a vivid and full-motion 360-degree augmented-reality viewing of the conflict zones provides context for the stories they are about to experience. Users then stand face to face with the augmented-reality version of the fighters as they talk with the director, whose voice guides the conversation. With mobile phone in hand, the user can walk up to and around a fighter to examine him more closely, right down to the details on his clothing. All the while, the fighter keeps his gaze on the user and reacts to his or her movements, creating the impression of real person-to-person interaction. The user can also turn around at any time to meet the fighter’s opponent, who presents the other side of the coin in the conflict.

Through its strategy of facilitating positive exchanges on a global level, and being rooted in the concept of a vast peace offensive, the app makes such meetings possible around the world while laying the groundwork for the future of documentary and photography.

Fabien Barati Interview

Can you describe The Enemy virtual reality (VR) experience?

We put users in a large 300 m2 space and equip them with a “backpack” and a virtual reality headset. After an introductory explanation, users can enter three rooms, each one representing a different conflict. During the experience, users can see each other but cannot interact or collaborate. With the help of images and the voice of Karim Ben Khelifa, users are introduced to six fighters, two for each conflict zone. The fighters then arrive in “flesh and blood” in the room and the users meet them. The fighters actually talk to the users and look at them. Each fighter behaves differently and has a small degree of artificial intelligence, which make him very lifelike. The sense of presence is really powerful. It’s like standing in front of a real person.

How does The Enemy differ from Emissive’s other virtual reality projects?

It’s different right from the get-go. We usually work on VR projects for the fields of communication and training. The Enemy is more like a documentary, and we are the co-producers. From a more technical perspective, we’re the only ones creating multiuser VR in a large space. Everything is new, even the hardware: the virtual reality headset, the backpack, you name it. The project took an extensive amount of research and development.

What is the backpack exactly?

It’s a recently released model of the MSI VR One computer. It’s extremely powerful—kind of like a gaming computer—and it has beautiful, fluid graphics. What made this computer really work for us was that it runs on battery power, and you can change the battery on the fly. You don’t have to turn off the computer to change batteries during the experience. The backpack connects to the user’s VR headset and works with a tracking system on surfaces of several hundred square metres.

How does the tracking system work in the space?

Since the computer has to know exactly where the user is in order to send the right image, we use an OptiTrack motion-capture system with the VR headsets. This requires placing a number of infrared cameras in this large space to detect the small positioning balls on the headset. Each user has different ball positions or “constellations,” which the system can distinguish and pinpoint in space. There is also a server running all of the users’ backpacks. It retrieves this detection data in the space and sends it back to each user. It also lets you begin and end the experience, or to restart it if needed.

During the three years you spent developing The Enemy, what were the biggest changes in the hardware used?

Before we had access to the backpack, we developed a wired experience. Users wore the first version of the Oculus, wired to a computer. This obviously complicated things because we had to worry about the wire, and it limited us to a single-user mode. Then we tried a multiuser test with laptops, but it was also less than ideal, especially because normal batteries are too weak. It took an electric bicycle battery and a transformer. Not only that, but it was also very heavy—it weighed nearly ten kilos! Only just recently we got the backpack, which made everything much easier. The Oculus headset also evolved. Initially, we used the DK1, then the DK2, and now we have the third version, which is a commercial version. It’s light, comfortable and has excellent resolution.

What were the main challenges of creating The Enemy?

Managing the hardware. Motion capture, virtual reality, wireless, multiuser mode… It was a huge challenge! But another challenge was making the fighters seem real—not just in terms of how they looked, but also how they moved. All of the characters in The Enemy are real fighters, and they move just like their subject does in real life. Several graphic designers and animators worked on recreating them from different sources. When we went to the actual combat zones to interview the fighters, we did a lot of photography, photogrammetry, 3D digitization and video. We collected an enormous amount of data in order to achieve extremely accurate results.

Did the experiment have any sound challenges as well?

A sound designer was in charge of regulating all of the sounds, such as Karim’s and the fighters’ voices, as well as those of the translations. All of the fighters speak in their native language, which had to be translated. There is very little sound and no music in The Enemy. Users have integrated headphones in their Oculus headsets, so to make the experience more immersive all of the sounds are spatialized. From our end, we had to make sure the sound worked in space and time and changed in volume in a realistic manner. It was very different than working on the sound of a film; it took a lot of tweaking.

Did you make any interesting discoveries while creating The Enemy?

We learned a lot in terms of content—what users can see and do. The system we use is very rare. There are only two other projects in the world that are similar to ours. People who test The Enemy are going to experience something they’ve never seen before—and probably won’t again for quite a while. We’ve been doing virtual reality for a long time at Emissive, but not at this level. We had to really analyze the behaviour of users and try to imagine what they would do.

We also learned a lot about the user experience—how to make it more fluid, effective, and appealing. We made a ton of adjustments and changes to the entire content and experience. Ninety-five percent of people have a very respectful attitude toward the fighters. Instead of testing the technology to see what it can and cannot do, people listen carefully, as if they were standing in front of a real person. There were even a few users who were quite scared! The experience lasts a little over 45 minutes, and when you come out of it, it’s important that you’ve learned something—that you’ve changed a bit as person and can say something positive about it.

Nicolas S. Roy Interview

What were your main goals when creating The Enemy app?

At the beginning of the project, we had to decide whether The Enemy would use virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), or both. After discussing it with Karim Ben Khelifa, we realized that it was important to include an AR experience. The VR version is really interesting and can travel to a number of cities, but the AR version is accessible to anyone worldwide with a smart phone. Our main goal was to make the experience accessible to as many people as possible. The application can be downloaded on Apple or Android, and can even reach people in the conflict zones—something that would otherwise be impossible.

How did you decide which technologies would best serve the project?

One of the problems with AR is that even though it has been around for a few years, the technology is not very advanced. The tools are not yet fully developed, and we are directly dependent on the evolution of phones. Until just recently, the only way to run the experience was to point at a marker—a QR code—to display an object, photo, or video. It’s only been very recently that AR has been possible without a marker. This makes the experience much more convincing. It’s as if objects magically appear in our environment! The technological choices we made for The Enemy were limited by what was available, so we decided to develop two versions using two different technologies.

What are the main differences between these two versions?

The first version uses very advanced hardware technology called Google Tango. It’s a device with a camera and a sensor that tells the tablet its exact location. It knows where it is in the 3D space and can recognize objects. We were able to use this tool to develop a very solid version of the app. The fighters are placed in our environment and we can walk around them. If feels like they are really standing there—in our home, in the park, or wherever else we might decide to use the app. This version works really well, and we can take it to festivals and let people try it. Unfortunately, this technology is not available on most phones yet, so we had to create a second, more simplified version that works on today’s phones. In this version, the characters are simply placed around the user when he or she turns around.

Were these two versions of the app developed in parallel?

Yes. The work was done in parallel throughout the project: both versions have shared parts but also different “branches.” We had to do this to adapt the app to the devices that would be available on the market when it launched. We are currently waiting for the iPhone 8, which is supposed to offer an experience similar to what we’ve done with Google Tango. It will make this much more convincing AR widely accessible. There are also augmented or mixed-reality glasses like Microsoft’s HoloLens that can do what we want to do, but they cost thousands of dollars! For sure, there are great options out there, but only if you’re willing to pay and accept the fact that the experience will be available only to a limited number of people. We had an entirely different goal for The Enemy, though.

How did you test the app, and what did you learn from these tests?

We had no choice but to test as we went along to see how users understood the scenario and interacted with the application. We also had to try to imagine the pace at which they used the app and how they would share The Enemy after the experience. The tests revealed several types of “human” constraints that required us to make some adjustments. For example, people are not used to holding their phones straight out in front of them the way we wanted them to. Instead, we tend to hold our phones closer to our body and look down at them at a 45-degree angle. Holding phones straight out wasn’t natural for people, and users got tired quickly. So we added pauses and audio-only sequences so that users could rest.

We also initially considered using cardboard glasses because they’re cheaper and accessible to more people. But users weren’t keen on wearing them in public. Which was a problem, because we wanted people to have the experience elsewhere than at home. A headset would be ideal, but again, it’s a human constraint. People don’t want to wear one.

Did you run into any major obstacles during development?

To create an app like The Enemy we relied on libraries and technologies that are still being developed. Augmented reality as we use it raises the issue of artificial vision. How does the computer see its environment, and how can it recognize specific objects just as the human eye would? Locating a chair, differentiating the floor from a table, etc. These are extremely complicated problems, and there’s a number of Ph.D. programs and companies out there that are entirely dedicated to this.

When we first started out, there were two companies offering technology that would work well for The Enemy. Unfortunately, they have since been bought out and are no longer accessible. One was Metaio, which was acquired by Apple. The other, 13th Lab, was acquired by Facebook. In other words, the only two relatively adequate technologies that could be used with a basic phone disappeared just a few months after the project began. Talk about a hurdle! In the end, we used Vuforia, Kudan and a free Google VR library.

How do projects like The Enemy change the way we use augmented reality?

Keep in mind that The Enemy is one of the first AR projects involving a great deal of narration. In Web and VR, there are codes for telling stories, but in AR everything was new. We were in completely unchartered territory. Also, most applications in AR are designed for playing or for promoting a product. Our goal with The Enemy was completely different. We wanted to convey a message, not to sell anything. I think AR is a fantastic tool for sharing information and that this use will only grow in areas like tourism, history, journalism, archives, etc. Whereas VR isolates you and transports you to another world, AR is more collective. It adds a new touch to our reality, gives new meaning to familiar things and infuses new life into places. In the case of The Enemy, it allows us to meet people we otherwise never would.

Trailer

Images

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Loading...

Download

Team

Karim Ben Khelifa

Author/Director

Photo

Louis-Richard Tremblay

Producer (NFB)

Photo

Photo : Angel Carpio

Chloé Jarry (Camera Lucida)

Producer

Photo

Fabien Barati (Emissive)

Executive Producer

Photo

Nicolas S. Roy (Dpt)

Executive producer and creative director

Photo

Antonin Lhôte (France TV)

France TV

Photo

Credits

A PROJECT BY

Karim Ben Khelifa

CAMERA LUCIDA

Executive Producer

François Bertrand

Producer

Chloé Jarry

Project Manager

Hélène Adamo

Production Manager

Vincent Décis

Assisted by

Silvia Alba

Caroline Bouffard

Productions Assistants

Thibault Bernard

Ana-Maria de Jesus

Matthieu Mainpin

Alexandra Ternant

Alessandra Bogi

Production Coordinators

Céline Delaunay

Frédérique Dewynter

Production Administration

Valérie Sieye

Anthony Donato

Stéphanie Garcia

VR Experience Distribution

Hélène Adamo

Stage Assistant Paris

Tennessee Charles

Communication

Hélène Adamo

Assisted by

Charlotte Zipper

Graphic Designer

Gordon

FRANCE TÉLÉVISION NOUVELLES ÉCRITURES

Production

Antonin Lhôte

Pierre Block de Friberg

Céline Limorato

Catherine Mugler

Sandrine Miguirian

Vanille Cabaret

Technical Coordination

Pascal Voisin

Communication

Agnès Desplas

Léo Fauvel

NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA

Executive Producer

Hugues Sweeney

Producers

Louis-Richard Tremblay

Marie-Pier Gauthier

Production Managers

Nathalie Bédard-Morin

Marie-Pier Gauthier

Editorial Manager

Valérie Darveau

Head of Technologies

Martin Viau

Production Coordinators

Caroline Fournier

Dominique Brunet

Perrine Bral

Administrator

Marie-Andrée Bonneau

Technical Coordinator

Mira Mailhot

Marketing Managers

Tammy Peddle

Paule Béland

Assisted by

Florent Prevelle

Social media strategists

Kathryn Ruscito

Emilie Nguyen Lamoureux

Press relations

Marie-Claude Lamoureux

Information technologies

Sergiu Suciu

Legal services

Peter Kallianiotis

EMISSIVE

Executive Producer

Fabien Barati

Project Managers

Didier Mayda

Jennifer Havy

3D Graphics

Vanessa Jory

Jean-Baptiste Sarrazin

3D Animations

Clotilde Steffen

Christophe Devaux

Development

Karim Guennoun

Charles Taieb

Clément Barbisan

Vincent Ponsort

Nolwenn Bigoin

Antoine Ferrieux

Technical Expert

Fabien Barati

Anthony Bousselier

DPT.

Executive Producer and Creative Director

Nicolas S.Roy

Production Managers

Geneviève Trepanier

Stéphanie Emond

Artistic Director

Maude Thibodeau

UX and Design

Maude Thibodeau

Raed Moussa

Julie Delias

Main Developper

Paul Georges

Development

Vander Amaral

Guillaume Tomasi

Julien Robitaille

SHOOTING IN ISRAËL / PALESTINE

Director

Karim Ben Khelifa

Assistant Director

Sélim Harbi

DOP Shootings

Jean-Gabriel Leynaud

Assisted by

Quentin Esperse

Photogrammetry and 3D Scan

Fabien Barati

Location Manager

Eman Mohammed

Rubi Makeover

SHOOTING IN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO

Director

Karim Ben Khelifa

Assistant Director

Sélim Harbi

DOP Shootings

Jean-Gabriel Leynaud

Assisted by

Quentin Esperse

Photogrammetry and 3D Scan

Fabien Barati

Location Manager

Adolph Basengezi

SHOOTING IN SALVADOR

Director

Karim Ben Khelifa

Assistant Director

Sélim Harbi

DOP Shootings

Quentin Esperse

Location Manager

Paula Rosales

POST PRODUCTION UNIT IMAGE AND SOUND

DOP Unity Environment

Lionel Jan Kerguistel

Translations

Rhona Dumonthier-Finch

Keren Gitai-Mock

Bianca Jacobson

Emmanuelle Ricard

Elizabeth Young

Gabrielle Lisa Collard

Bronwyn Haslam

Rhonda Sherwood

Jovana Jankovic

Anna Victor)

Catherine Bélanger

Crystal Beliveau

English Voice for VR Instructions

Fanny Gautier

French Voice for VR Instructions

Cassandre Manet

French and English Voice Over

Alexandre Daneau

Peter Michael Dillon

Matt Holland

Gabriel Lessard

Actor’s Agents

Voices

Tandem

Emilie Françoise

Vocal Coach

Benoit Rousseau

Élise Bertrand

Assistant Editor

Guillaume Cage

Sound Recording Studio

Sylicone

Pom’Zed

ONF

Sound Engineer

Philippe Chariot

Bruno Lagoarde

Matthieu Cochin

Eric Wager

Marie Muller

Head Grip

Vincent Blasco

Jean Chesneau

Technical Instruments

Optitrack – Natural Point

Human-Computer Interaction Producer

D. Fox Harrell, PhD

Impact Producers

Lina Srivastava

Tina Ahrens

Trailer and communication

Trailer #1

Trailer Director and Editor

David Fernandes

Assisted by

Hélène Adamo

Trailer DOP

Antoine Goetghebeur

Music

Running out de David Tobin, Jeff Meegan and Julian Gallant

© A music

Trailer Mixing

Bruno Lagoarde

Trailer #2

Sound Editing

Emmanuel Alberola

Editing

Marie-Ève Talbot

Trailer #3

Editor

David Fernandes

Video Excerpts

Jeffrey Trunell

Supported by the Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée

Nouvelles technologies en production et Fonds Nouveaux Médias

With the participation of DICRéAM

With the participation of l’Institut National de l’Audiovisuel (INA)

Supported by

The TFI New Media Fund

The Ford Foundation

The Sundance Institute New Frontier Program

The Doris Duke Foundation for Islamic Arts’

Doris Duke New Frontier Fellowship and the Open Society Foundations

MIT Open Documentary Lab

MIT Center for Art, Science & Technology

Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée

Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée

The Enemy has also been supported by Google Digital News Initiative.

For their help and support during the entire production stage, productions teams and the author wish to thank:

Voyelle Acker, Tina Ahrens, Antoine Allard, François Asseman, Pauline Augrain, Markus Badde, Antonin Baudry, David Beja, Pervenche Beurier, Ludovic Blecher, Léontine Bob, SokLinh Cheng, Olivia Colo, Maya Dagnino, Juan B. Diaz, Rémy Dorne, Mathieu Fournet, Aude Gauthier, Chantal Gishoma, Patrick Gonidec, Thais Herminie, Katherine Higgins, Ingrid Kopp, Jérôme Lecanu, Philippa Mothersill, Oumar N’Daw, Bruno Patino, Rémy Pflimlin, Alexis Raison, Christine Siméone, Kamal Sinclair, Michele Slatter, Caspar Sonnen, William Uricchio, Doug Weinstock, Sarah Wolozin.

The author would like to thank Boris Razon for his involvment to intiate the project

Production teams would like to thank the following institutions for hosting VR experience user testing in their facilities:

Le Forum des images (Corinne Béal and Michaël Swierczynski)

L’IRI – Institut de recherche et d’innovation du centre Pompidou (Vincent Puig and Nicolas Sauret)

Le Carrefour numérique² de la Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie (Bruno Maquart and Pierre Ricono)

L’INA – Institut national de l’Audiovisuel (Kanele Bazin, Amandine Collinet and Marie Tomat)

Special thanks to:

Abu Khaled

Gilad

Jean de Dieu

Patient

Jorge Alberto

Amilcar Vladimir

© Camera lucida productions/ France Télévisions / ONF / Dpt / Emissive – 2017

Media Relations

-

About the NFB

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) is one of the world’s leading digital content hubs, creating groundbreaking interactive documentaries and animation, mobile content, installations and participatory experiences. NFB interactive productions and digital platforms have won over 100 awards, including 21 Webbys. To access this unique content, visit NFB.ca.

-

Camera Lucida

CAMERA LUCIDA (PARIS) brings together producers and writer/directors who share a passion for innovation and artistic creation. The strategy is to push the boundaries of storytelling and to produce works in a wide range of formats, from interactive experiences to animation and IMAX® 2D or 3D.

-

Emissive

Specializing in virtual and augmented reality, Emissive designs and produces unique immersive experiences and supports clients in integrating these innovative technologies. Since its creation in 2005, Emissive has become a European leader in the VR industry. Its team of 25 experts create engaging applications, tailored to the needs of communication and training.

Emissive works with leading brands such as IKEA, Hermes, Dassault Systèmes, Merck, Thales, BNP Paribas, Patek Philippe and Orange.

-

FranceTV Nouvelles Écritures

FRANCETV NOUVELLES ÉCRITURES (PARIS) is France Télévisions’ narrative research department. Since 2011, it has co-produced and participated in the development of more than 170 native web, transmedia, interactive and linear projects. Nouvelles Écritures does not restrict itself to any one genre, using innovative approaches to show today’s world in a new light.

-

About Dpt.

Dpt. is a digital studio crafting award-winning immersive and narrative experiences. We conceptualize, design and build content-driven work for brands and museums as well as for the entertainment, film and education industries.